Different Strokes: the New Face of Cultural Competency

The focus of cultural competency efforts is shifting away from educating physicians on the differences between ethnic groups in terms of disease prevalence, and toward treating the individual patient. For time-challenged hospitalists, this poses several unique challenges.

By Kate Huvane Gamble

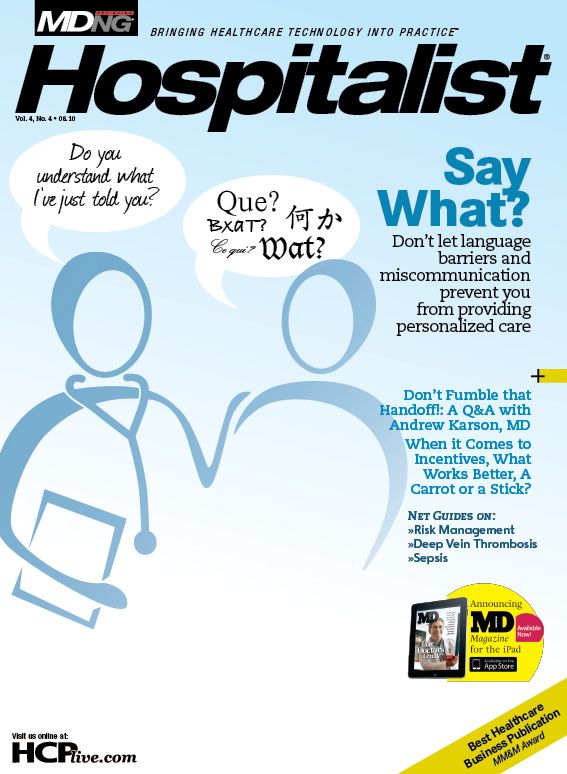

As the US patient population becomes increasingly diverse, both in terms of languages spoken and cultural beliefs that impact how patients wish to receive treatment, physicians face a greater challenge in providing quality care. But while the topic of disparities in care has been well-documented from a public health perspective, little has been written on how this issue affects hospitalists, who have a small window of time with each patient, and therefore may not be equipped to deal with certain issues. Beyond the obvious concern of language barriers, there are other matters—such as patients who have dietary restrictions due to religious beliefs, or preferences as to whether they are examined by a male or female physician.

It’s a lot to digest; and for physicians who operate in the fast-paced, often hectic hospital environment, these types of issues can create a significant roadblock.

To that end, a number of organizations have begun offering cultural competency training to enable physicians to have more effective interactions with a diverse group of patients, which in turn can help improve the quality of care delivered. The problem is that by learning about how some ethnic or racial groups are more prone to developing certain diseases, or how members of some religions prefer alternate treatments, physicians can get caught in a common trap.

“It can be very challenging to treat diverse populations, and I think one of the biggest issues for hospitalists is that sometimes people feel that based on what we’re seeing in the literature on racial and ethnic disparities, we should treat all of our patients the same,” says Alicia Fernandez, MD, professor of clinical medicine at University of California, San Francisco. “And in fact, what the literature means is that we may need to take the approach of different strokes for different folks, and focus on making sure that people get what they need while they’re hospitalized to improve their outcomes.”

Over the years, several studies have indicated that significant disparities in disease prevalence exist among racial and ethnic groups. To cite just a few examples, research has shown that genetic factors common to African ancestry may be associated with increased risk of kidney dysfunction in young black men (American Journal of Nephrology; that breast cancer outcomes can differ based on race and socioeconomic status (Journal of the American College of Surgeons); and that Hispanic women are more likely to present with heart disease risk factors at an earlier age than white women (Women’s Heart Foundation).

But although it is critical that physicians are educated about these findings, it is also important to realize that what works for one patient doesn’t necessarily translate across an entire ethnic group. “Our goal has to be effective care for all of our patients, irrespective of their racial or ethnic background,” says Fernandez, who is also a physician and former hospitalist at San Francisco General Hospital.

A big part of that, she believes, is understanding the needs of the patient as an individual, and tailoring his or her care accordingly. “For example, you might have an African American patient with a PhD in economics who requires very little explanation of why a particular test may or may not be definitive. But at the same time, you could have a low-income patient, white or black or any ethnicity, with low literacy, for whom it is much more challenging to explain a diagnosis or treatment plan.”

Breaking down the language barrier

However, while she doesn’t believe that a patient’s race, ethnicity, or religion should dictate the course of treatment, Fernandez does feel that there is a need for institutional cultural competence—particularly when it comes to making sure physicians can communicate effective with all patients.

A number of facilities employ professional interpreters to help break down the language barriers; but for hospitalists who are making rounds, it isn’t always possible to quickly track down a language specialist. “Consequently, a doctor might take short cuts by trying to speak with whoever is at the bedside, or using a staff member to interpret,” she says. As a result, the risk for error increases, and patient satisfaction rates tend to decrease.

In fact, many believe that understanding the language in which care is delivered can play a significant role in determining the quality of care patients receive. A study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in 2007 found that the majority of disparities that exist in access to prevention and chronic disease management services between whites and Latinos are due to the language barrier—even after researchers accounted for education, insurance coverage, and several other factors.

“I think people frequently underestimate how confusing an environment the hospital can be for many of our patients,” says Fernandez. “So many patients don’t understand what they’re being told, and so many don’t trust the institution, and all of that makes people less likely to follow instructions.”

It’s a problem that doesn’t appear to be subsiding anytime soon. According to projections made by the US Census, the foreign-born population of the US is expected to grow for decades to come, making it increasingly important for hospitals to provide physicians and patients with the tools and assistance needed to communicate more effectively. At San Francisco General Hospital, where more than 100 languages are spoken, both patients and healthcare providers can access the video translation system on monitors place throughout the wards, according to Fernandez.

At a number of institutions, electronic translation systems or phone services are being used to improve communication, according to Alpesh Amin, MD, professor of medicine and executive director of the Hospitalist Program at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine. In addition, “A lot of patient education material is now being offered in different languages,” he adds. “I think institutions are really trying to deal with the language barrier.”

Extending care outside the hospital walls

Effective communication can play a critical role in determining the quality of care patients receive, and for hospitalists, that communication doesn’t stop when a patient leaves the hospital.

“The advantage hospitalists have is that we oversee the patient’s care and see the patient several times a day, if need be,” says Amin. Where it can get difficult is when patients are discharged or transferred to a different facility. “There needs to be seamless communication between physicians to ensure that patients get positive outcomes.” Hospitalists, he says, need to discuss the next steps with the patient, confirm that he or she receives follow-up care, and maintain an open line of communication with the patient’s provider.

Fernandez agrees, adding that it is critical to verify that the patient’s data is sent to his or primary care physician. That way, “even if the patient doesn’t fully know everything that happened during the hospitalization, the primary care physician is aware of it.”

This type of communication can be easier to facilitate for hospitals and physician offices that are part of a closed health system, particularly if a system-wide EMR is in place. But whether data is being transferred electronically or via fax, the important thing is that the patient’s care team is working together to provide him or her with the best possible care.

The key, says Amin, is “to develop a system and a will and a want to improve communication. There needs to be a system component and a culture component. The physicians have to want to do this, and the system has to be willing to develop that opportunity by providing the tools that are necessary.”

For hospitals that treat diverse patient populations, post-discharge care presents an added challenge, particularly for those who don’t have a primary care provider or lack adequate health insurance. And sometimes, even that isn’t enough to level the playing field. A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that among Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans, African American patients were less likely than white patients to receive follow-up care after a hospitalization for mental illness or to undergo breast cancer screening. Additionally, African American patients who were diabetic were less likely to undergo eye exams after leaving the hospital, and those who had suffered a heart attack were less likely to receive beta-blocker medication.

In light of these findings, achieving optimal outcomes following discharge may seem like an uphill battle; however, some organizations are taking measures to improve patients’ understanding of follow-care care instructions in an effort to improve adherence and overall health. One of those organizations is Boston Medical Center, which is piloting an interactive video program for this purpose, according to Fernandez.

“There technologies are going to be very helpful,” she says. However, it’s going to take more than that. “We need to be aware that many of these patients may actually require more of our time, which is really hard on us.”

Speaking up

That extra time, she points out, often goes uncompensated, which puts physicians in a difficult position. But instead of taking shortcuts with patients who don’t comprehend care instructions, Fernandez urges hospitalists to speak up. “I think that every physician should start by advocating within the quality committee of their hospital, because this is a quality of care issue,” she says. “A hospital really needs to be able to provide us with the type of environment under which we can deliver effective care without taking hours and hours. Pointing this out, and saying, ‘hey guys, we really need a discharge coordinator who absolutely makes sure that patients have an appointment with their outpatient physician and sufficient medication’—that’s a very concrete thing people can do.”

Fernandez also encourages physicians to contact their state medical societies to learn what is being done on a national advocacy level, or join efforts headed up by organizations such as the American Medical Association and the American Hospital Association (see sidebar below) to help eliminate disparities in care.

Finally, physicians can become involved by participating in organization-wide cultural competency training efforts such as group sessions, online training programs, and e-mail updates designed to help physicians more effectively relate to and communicate with a diverse group of patients.

“Cultural barriers certainly impact how we do treat patients and having knowledge of diversity or cultural issues is really important in the process of patient care,” says Amin. “We should be sure that we engage in trying to learn about cultural differences; that’s part of being a good MD.”

The Changing Demographic Profile of the US

The US population is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse. According to information gathered by the Congressional Research Service, around 81% of the US population was white in 2000; by 2050, that figure is projected to fall to 72%. Increases will be most dramatic for Asians and for those who fall under the category that includes American Indians and Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, and individuals who identify with two or more races.

Additional Resources on Cultural Competency and Disparities in Care

- Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals

- AHRQ: Minority Health

- American Medical Association: Eliminating Health Disparities

- American Hospital Association: Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities