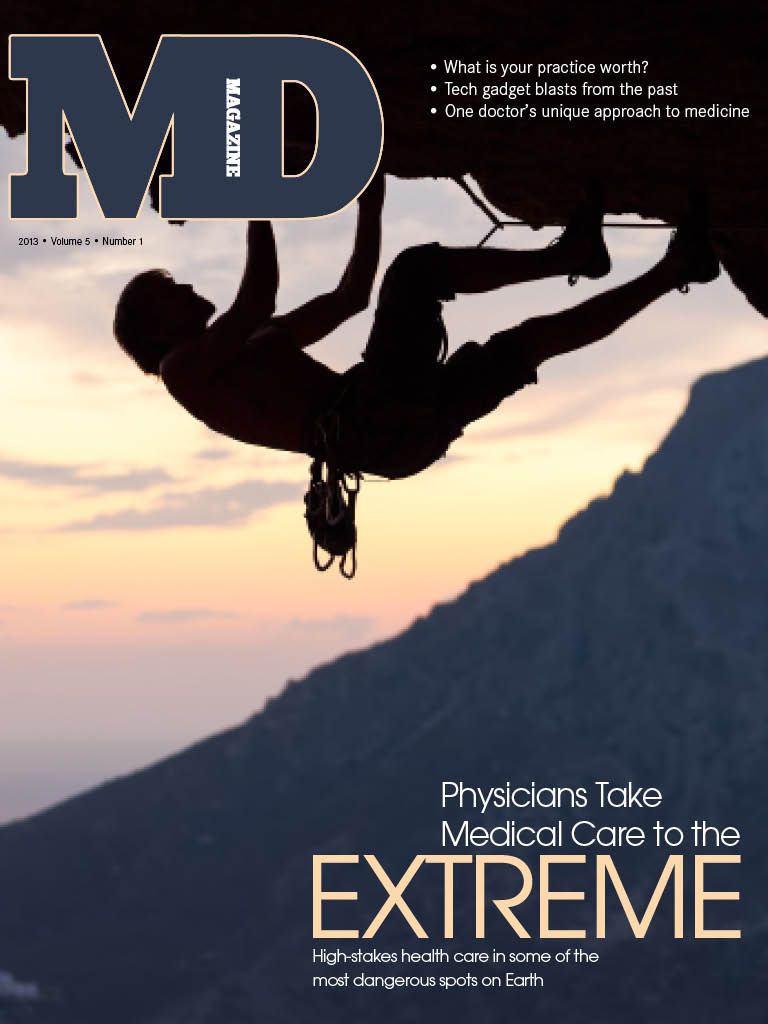

Physicians Take Medical Care to the Extreme

High-stakes health care in some of the most dangerous spots on Earth.

Christopher van Tilburg was at a crossroad. He was struggling through medical school, attempting to balance his studies against his desire to go wind surfing and skiing around the world. He had already delayed his entrance into medical school for a year in order to travel, and that thrill of the outdoors and the love of adventure were still present.

Then, while working on a school project, he stumbled upon a journal in the University of Washington medical library. The journal was The Journal of Wilderness Medicine (known as Wilderness & Environmental Medicine since 1995), and suddenly everything clicked. “It was like, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s this group of physicians out there interested in doing what I want to do,’” van Tilburg recalls. “I just stumbled upon it by accident.”

The year was 1990, and van Tilburg’s “stumble” paved the way for a career in wilderness and emergency medicine—highly specialized fields for which an increasing number of physicians are heeding the call.

What’s the allure?

Karen Spangle, MD, is an emergency medicine physician who also specializes in wilderness medicine at Loyola University Health System. Raised in what she calls an austere environment in Wyoming, Spangle has served two tours of duty as a physician in Iraq. She says there are basically two types of people: those who run toward disasters, and those who run away from them.

“I think that most people who are involved in emergency and wilderness medicine are the type who tend to run toward disasters; they just want to help,” explains Spangle, who admits that the desire to run toward disasters was something she tried to deny in herself for a long time. “I never considered myself to be somebody who sought out that kind of experience, but I guess in some ways it is a calling.”

Luanne Freer, MD, also heard the calling. Literally 12 hours after graduating from a joint residency program at George Washington University, Georgetown University, and the University of Maryland (all three have since developed their own programs), she loaded her Jeep, drove west, and took a job at Yellowstone National Park. There she discovered that she could combine her passion for the mountains and wilderness with her medical profession.

“It was one of the pivotal points in my life. It really opened my eyes,” says Freer, who is currently medical director for Medcor Inc. at Yellowstone, and founder of the Everest Base Camp clinic. “Even though I went back east to fulfill a commitment for a faculty job at George Washington, I still pined for the west. I ended up resigning my job in Washington, DC, and headed west for good.”

Learning on the job

Van Tilburg recalls that in order to become an expert in wilderness medicine he had to piece things together himself. Today there are formalized programs offered by institutions such as the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, where a diploma in austere and mountain medicine can be obtained through the school’s Emergency Medical Services Academy. But that wasn’t the case in the early 1990s.

“I took an international medicine elective, and I designed some of my own electives, including a ski patrol elective,” van Tilburg says. “I went to as many national conferences as I could. I started self-educating myself by writing stories and articles. I wrote articles on wilderness medicine in every form you can imagine. I wrote scientific articles for medical journals, and lay articles for news magazines.”

The writing paid off. Today van Tilburg, who is based in Oregon’s Hood River Valley, is the editor of Wilderness Magazine and the author of the book Mountain Rescue Doctor (St. Martin’s Press, 2007). The latter recounts some of his most dramatic rescues, including one in which his team responded to an individual with a back injury in a mountain canyon in the middle of a 20-foot-deep pool of water.

“We were faced with taking this person up an extremely dangerous cliff, and I just thought to myself, this is not safe for anybody… me, the patient, or my colleagues,” van Tilburg recalls. “And it was one of the few times where I was really, really scared. We ended up halting the cliff rescue and waiting two hours for a floating stretcher, which was very hard to find in a small, rural county. And we just stopped the cliff rescue and hauled the patient out with the floating stretcher.”

Van Tilburg is a member of the Crag Rats, the oldest mountain search and rescue organization in North America. He says that the unit has a mantra it will never violate: Self first, team second, patient third.

“Every year we have rescues where we say we’re not going out after that patient after dark; we’re waiting until it’s light out,” van Tilburg says. “Or we’re not taking the shortest route to get to the patient; we’re going to take a longer route, because the shorter route is not safe. So we put our own safety as the first priority.”

Safety at high altitudes

Freer is well versed on the importance of safety. She did her first research project at Yellowstone on the incidence of altitude sickness after recognizing the significant number of people who suffer even mild effects while at the park on a family vacation. It was during the presentation of that research at a Wilderness Medical Society conference in 1999 that her career took a dramatic turn.

Freer was approached by a member of the audience following her presentation. There was a group leaving for Nepal in 19 days and they needed a doctor to lead a volunteer clinic—did she want to go?

“That just changed my life,” Freer recalls. “It was my first exposure to the kind of extreme needs that are evident in the developing world.”

Freer made the trip, went back in 2002 and lived in a small village in Nepal for four months practicing medicine, and came up with the idea for putting an emergency clinic on Mt. Everest. The clinic opened on April 2, 2003—a medical facility in a landscape littered with ice and rock more than 17,000 feet in elevation. Those elements provided more than a few challenges.

According to Freer, the biggest challenges were figuring out how to keep things from freezing—everything from liquid medication to equipment. Wires and electronics become very sensitive in freezing cold and dry conditions.

“The very first year of the clinic, we were powering our equipment on a generator that, unbeknownst to me, was putting out way more voltage than it advertised, and we literally caught our laptop on fire, and blew up our SAT phone,” Freer says. But living on a glacier can be tricky, because sometimes the ice melts. “It got to the point where one day I walked into the clinic and found most of our medication under two inches of water. And all of our electronics were blowing up, and I thought, ‘Why am I doing this?’ I shed more than a few tears, and thought, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t be here.’”

But to this day Freer can answer that question by looking at a photograph of a 22-year-old man being carried unconscious into the clinic. He was dying of cerebral edema. Fortunately, the clinic team was able to save his life, and the man walked back down the mountain to his wife and two children. “I think the fact that somebody shot that photo in the midst of all this other mayhem was a tangible, visible reminder of why I was doing this,” Freer says.

Training under fire

Two tours of duty as a physician in Iraq, as well as working with and becoming an instructor for an organization called Advanced Wilderness Life Support, prepared Spangle for virtually anything. In particular, the military enabled her to become an expert at triage.

“It teaches you how to respond to multiple casualties at once,” Spangle says. “There’s rarely an instance where there’s a single person wounded. There’s usually multiple people coming in at the same time, and so you become an expert at recognizing the most critically injured, and sorting them out and treating them first. You also get very good at developing a team, because you’re only as good as the people you train, so I think that is one thing the military does exceptionally well, is training the subordinate medics and nurses and medical staff to maximize their potential so that they can do the most good.”

Spangle says the key to emergency medicine is thinking and acting quickly, sometimes making decisions with a limited amount of medical supplies available. There’s no time to think about the severity of any one incident in the moment it occurs because “you have to do so much so quickly. It takes away the fear of the practice, and left me very confident in my skills after I left Iraq.”

As for the danger aspect, Spangle keeps things in perspective. Her first tour was in 2005, and there was considerable shelling and bombing going on at that time. “It’s dangerous,” she admits, “but it’s not as dangerous as being an infantry solider or one of the pilots who are actually doing the hard work.”

Specialized training

The Austere and Mountain Medicine program at the University of New Mexico’s Emergency Medical Services Academy provides graduates with a diploma that is worth 15 college credits and takes about a year to complete. The curriculum, according to program manager Jason Williams, is taught at a very high level.

“What we’ve found is that it’s very easy to take a physician, a highly trained medical professional, and teach them about wilderness medicine,” Williams explains. “You can have a lecture about it all day long. But at the end of the day actually taking them into the environment, exposing them to the elements, and making them do patient scenarios and different diagnoses in extreme environments is very different for a physician, and that’s really what our programs have to be focused on.”

Those eligible to enroll in the program are physicians, nurses, and paramedics. Requirements include having previously worn a pair of skis. Knowledge of rock climbing is not a prerequisite, but enrollees need to be comfortable working in a vertical setting or it’s doubtful they’ll be able to pass the course. By the time they graduate, however, medical professionals must be able to rock climb at a proficient level, be able to land a helicopter in certain environments, or know how to set up helicopter staging areas.

“The good thing is, if somebody were to take the diploma in mountain medicine program, they would be trained very highly in the mountains, and they will absolutely be proficient going over a cliff face to rescue an injured patient and provide medical care at the same time,” Williams says. “But at the end of the day the practical experience of being able to provide care to these patients in austere environments can be transferred to any disaster situation, Third World medical situation, rural healthcare situation… it applies to everything.”

Most rewarding

The common element that doctors van Tilburg, Freer, and Spangle share is their passion for their work. They recognize that what they do is unique, and they derive extreme personal gratification from the care they’re able to provide.

“I do this because I feel like it’s an area that not only am I good at, but it’s an area where I can really make an impact on the health and safety of people. I bring passion to it. I take it seriously, and I put a lot of time and effort into it. It’s the place where I feel I can make a difference in medicine,” van Tilburg says.

Caring for soldiers, says Spangle, will always be one of the greatest honors in her life. “I would never undo or trade the experience.”

As for personal accomplishment, Freer says she has not yet climbed to the summit on Mt. Everest, which is more than 29,000 feet in elevation, and is not certain she will ever accomplish that feat. “I’ve made a personal decision not to climb with oxygen,” she says. “I believe that there are only a few people on Earth who are resilient enough to climb (to the summit) without oxygen, and I know I’m not one of them. People endure a lot of suffering to get up that mountain, and I would like to go up higher, but I’ll also be just fine if I don’t.”