How HIV Gets the Opportunity to Infect Macrophages

Macrophages' protective protein can get turned off, but it's unclear how that happens.

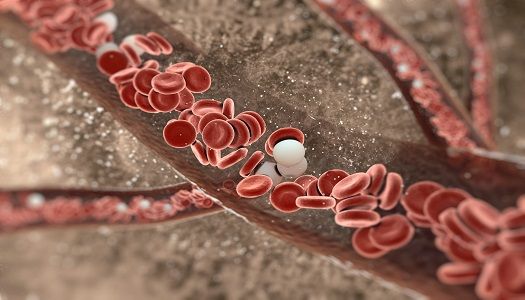

Even macrophages—an altered white blood cell that becomes an important part of the immune system when an infection is detected—aren’t safe from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Researchers first discovered that HIV can infiltrate macrophages in the 1980s, but the topic didn’t come to the forefront until a few years ago. In a new study, a team from the University College London (UCL) found that although macrophages have a protein that shields them, the virus is able to make it past the defense.

The protective protein, SAMHD1, acts as an antiviral and inhibits HIV replication.

“Other viruses can disable SAMHD1, but HIV cannot,” lead author, Petra Mlcochova, a post doc at UCL’s Division of Infection & Immunity, said in a news release. “Our work explains how HIV can still infect macrophages, which are disabling SAMHD1 by themselves.”

Although HIV can’t disable SAMHD1, the UCL team found that the protein’s antiviral protection stops when the protein is switched off. But how does SAMHD1 get switched off? And why? Those answers are unclear, but the researchers speculate that it happens when macrophages perform the natural function of repairing damaged DNA.

“We knew that SAMHD1 is switched off when cells multiple, but macrophages do not multiple so it seemed unlikely that SAMHD1 would be switched off in these cells,” said senior author, Ravindra Gupta, MPH, BM, a professor at the division.

“And yet we found there’s a window of opportunity when SAMD1 is disabled as part of a regularly-occurring process in macrophages,” he noted.

When a macrophage becomes infected with HIV, it continues to produce the virus. This may not be an issue in most patients with HIV, Gupta explained, but focusing on macrophages could help lead researchers to a cure.

A study published in the Journal of Virology found that HIV hides in brain tissues even when the virus is undetectable in the blood. The brain also has macrophages, in the form of microglia. Many infected brain cells are this type of macrophage, which further makes a case for developing treatments with the white blood cell macrophages in mind.

Previous research has shown that histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, which are sometimes used to treat cancer, can reactivate latent HIV in order to perform a “shock and kill” strategy. In another part of the UCL study, the researchers explored the use of HDAC inhibitors for HIV in human cells in vitro and mouse brain tissues. They found that macrophages responded to the inhibitors, showing that the drugs could help inhibit the virus’ opportunity to infect macrophages.

“While this is a barrier to achieving control of HIV in just a minority of patients, it may more importantly be a barrier to a cure,” Gupta concluded.

The study, “A G1-like state allows HIV-1 to bypass SAMHD1 restriction in macrophages,” was published in The EMBO Journal. The news release was provided by UCL.

Related Coverage:

The HIV That We’re Not Talking About