How the Law Should Handle the Opioid Epidemic

While the opioid epidemic has had a devastating impact on American families, there is some hope that the future is bright.

America is in the midst of an opioid epidemic, which has led to a shortening of life expectancy, especially for those aged 44 years or less.

The good news is that we know how to deal with epidemics through treatment and prevention. For cases of opioid addiction, treatment with buprenorphine or methadone, known as medication assisted treatment (MAT) is associated with fewer overdose deaths as compared with traditional abstinence-based treatments.

However, these medications are underused, and strategies need to be developed to increase the use of these life-saving medications. Appropriate opioid prescribing habits for pain management have the potential to prevent the healthcare system from producing new cases of opioid addiction. Current prescribing practices will need to change.

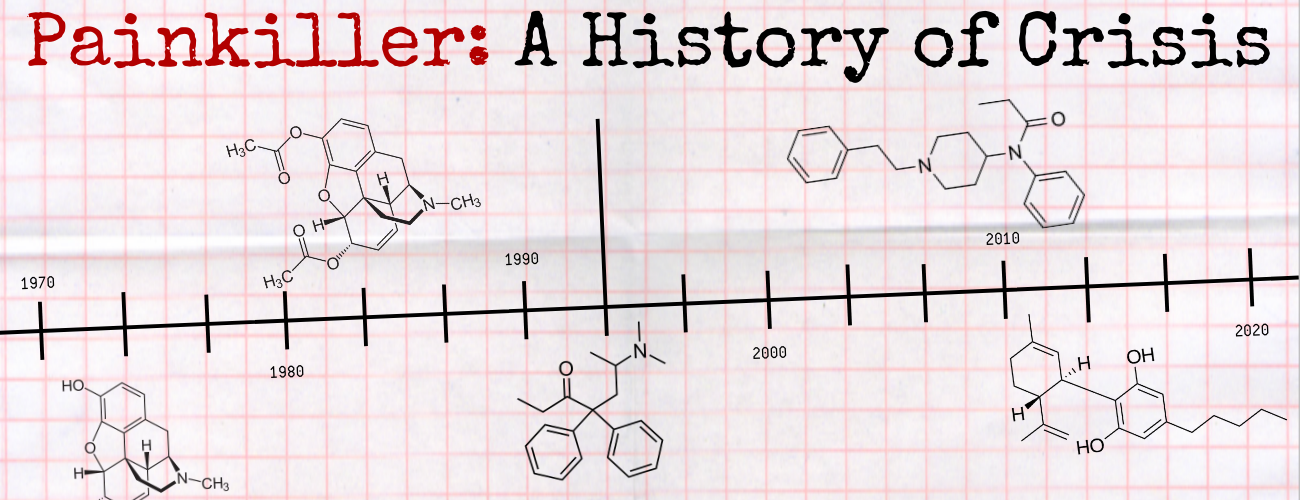

This is the second time America has experienced an opioid epidemic. The first epidemic occurred in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when addictive substances were freely available without prescription. The 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act controlled availability of these drugs.

In the 1930s the Food and Drug Administration was established to further regulate these drugs and its authority was strengthened with the 1951 Durham-Humphrey Act. This legislation helped to prevent the healthcare system from producing new cases of opioid addiction. In those times individuals with an opioid addiction might run afoul of the law, and their condition was treated not as a medical condition but as a criminal matter.

The thinking that those with an opioid use disorder have a criminal condition and not a medical condition persists today. Quite often, those who are arrested are placed in a cell to experience drug withdrawal without treatment, sometimes with fatal consequences.

Many jurisdictions established a “drug court” as an alternative to the criminal courts, and a handful of jurisdictions have developed an “opioid court” specifically to deal with defendants who have opioid addiction. However, these courts tend to rely on traditional abstinence-based treatment programs instead of MAT, which represents a huge missed opportunity for “therapeutic jurisprudence.”

Ideally, those arrested who have an opioid use disorder would be treated as someone with a treatable medical condition. They would have their opioid withdrawal treated medically when first incarcerated, and then started on MAT. Some falsehoods would need to be addressed including: 1. It is appropriate to allow arrested individuals to suffer from untreated withdrawal and 2. Using MAT is like substituting one drug for another. Untreated withdrawal can be fatal, and this obviously is of no benefit to the individual. It is true that using buprenorphine or methadone for MAT is like trading those drugs for heroin or fentanyl.

However, MAT is associated with a reduced risk of death from overdose, lower rates of hepatitis and HIV infection, a reduced risk of committing additional crimes, and improved function in society.2 Many patients on MAT would like to come off of buprenorphine or methadone; however, many find it useful to first stabilize other aspects of their lives (e.g. criminal, financial, employment, education, interpersonal) before attempting to lead “drug-free” lives.

Richard Blondell, MD, is the Professor Emeritus of Family Medicine at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo. The presented analysis reflects his views, not necessarily those of the publication.  Health care professionals and researchers interested in responding to this piece or similarly contributing to HCPLive® can reach the editorial staff by submitting a request here.