Iliopsoas Bursitis

Anterior hip pain sometimes arises from iliopsoas bursitis, which may present as a groin mass. Pain may be referred to the abdomen, thigh, or knee.

A healthy 40-year-old active-duty male soldier presented with a painless groin mass, which he had noted a few weeks earlier. He denied having constitutional symptoms, recent infection, inflammatory joint symptoms, or a history of trauma.

The physical examination was notable for an immobile firm mass in the patient’s right inguinal area. There were no other areas of lymphadenopathy, and the results of a genitourinary examination were normal.

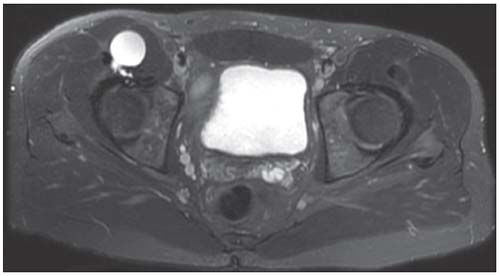

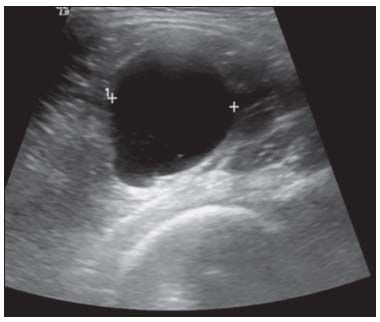

Radiographs of the patient's right hip and pelvis were obtained; the results were unremarkable. An ultrasonogram (top) and an MRI scan (bottom) were obtained.

The ultrasonogram of the patient’s right groin revealed a well-defined, lobulated, anechoic cystic structure that measured 4.3 × 2.8 × 2.9 cm posterior to the iliopsoas muscle, without communication with the hip joint. The MRI scan, an axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted image, confirmed a diagnosis of iliopsoas bursitis.

Iliopsoas bursitis is a somewhat uncommon and unrecognized cause of anterior hip pain that also may present as a mass lesion. The iliopsoas, or iliopectineal, bursa is located between the anterior capsule of the hip and the iliopsoas muscle bilaterally in 98% of adults.1 It begins superiorly at the inguinal ligament and extends to the lesser trochanter of the femur inferiorly while lying between the iliofemoral and pubofemoral ligaments. Flanking this bursa are the femoral artery, vein, and nerve.

Patients typically present with anterior hip pain worsened by activity or a groin mass or both. If pain is present, it may be localized on physical examination to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and may be exacerbated by hip movement, especially extension.1 The anterior hip pain may be referred to the abdomen, thigh, or knee as a result of femoral nerve entrapment and may lead to a shortened stride on the affected side.2-4 To relieve pain, patients may passively hold their hip in flexion, adduction, and external rotation, because this decreases tension of the overlying iliopsoas muscle.1

Physical examination also may discern a palpable or audible snap in the hip region.3 The groin mass usually is painful and may cause venous obstruction, femoral neuropathy, and compression of abdominal organs, depending on bursa size and extension.1 The iliopsoas bursa occasionally may rupture or become infected.2

The main causes of iliopsoas bursitis include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), trauma, total hip arthroplasty, and overuse injury.1,3 Because of the nonspecific presentation and location of iliopsoas bursitis, this condition is an often overlooked cause of symptoms involving the inguinal area, abdomen, and lower limb.2 The differential diagnosis includes various types of hip joint pathology, such as snapping hip syndrome, trochanteric bursitis, lumbosacral radiculopathy, inguinal hernia, appendicitis, gynecological pathology, undescended testes, and femoral artery aneurysm.5

Three-dimensional imaging is helpful for confirming the diagnosis of iliopsoas bursitis and may reveal communication with the hip joint. The iliopsoas bursa is located near the most vulnerable portion of the anterior capsule of the hip; therefore, a defect in the anterior capsule leads to communication between the bursa and the hip joint.1 The hypothesized pathological mechanisms by which such a communication may occur include friction from the overlying iliopsoas tendon, increased intra-articular pressure from overproduction of synovial fluid, and a weakening of the capsule resulting from wear with age or inflammatory or degenerative joint disease.1,6

A study conducted by Wunderbaldinger and associates6 examined 18 patients with iliopsoas bursitis with ultrasonography (US), CT, and MRI. A communication with the hip joint was seen in 56%, 60%, and 100% of patients with US, CT, and MRI, respectively. The communication between the bursa and hip joint seen on MRI was surgically confirmed in all 18 patients.

A communication between this bursa and the hip joint is present in about 15% of healthy adults, suggesting that the communication may predispose to this condition. In their study, Wunderbaldinger and associates6 found that US and CT typically underestimate bursa size and that MRI is the most accurate in detecting size. Imaging was helpful in determining the cause in some of the cases, including degenerative OA, chronic inflammatory polyarthritis, and acute bacterial arthritis.

Overall, MRI is considered the imaging modality of choice in iliopsoas bursitis.6 However, US is the quickest, most cost-efficient imaging method for estimating size and the impact on surrounding structures.

Treatment of patients with iliopsoas bursitis is individualized according to the cause, pain severity, and associated symptoms in specific patients. The framework of iliopsoas bursitis treatment starts with conservative measures, such as rest and avoidance of exacerbating activities, oral NSAIDs, and local physical therapy.3 In a study conducted by Johnston and colleagues,7 a home-based hip rotation strengthening program improved pain and function in 77% of patients. These measures usually are sufficient in treatment for overuse injury.

If hip OA is the cause or if the symptoms are severe, US-guided aspiration, possibly with injection of corticosteroids and anesthetic into the iliopsoas bursa, is an option. Adler and coworkers8 demonstrated that this latter treatment is safe and effective, although results vary with operator experience and technique. If the cause is inflammatory polyarthritis, such as RA, the above-mentioned conservative measures would be recommended, along with adequate control of the underlying arthritis with chemotherapeutic agents.

Refractory iliopsoas bursitis may require a surgical intervention, such as bursectomy, capsulectomy, or synovectomy-possibly with iliopsoas tendon release-or total hip arthroplasty.7 More invasive therapeutic modalities may be required if there are associated symptoms resulting from venous obstruction, femoral neuropathy, or compression of abdominal organs.6

Because pain developed in our patient with the use of his hip flexors, US-guided aspiration of bursal fluid was performed, followed by injection of 2 mL of bupivacaine and 1 mL of triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg/mL). About 22 mL of yellow, gelatinous fluid was aspirated, and the culture was negative. After the injection, the patient had complete resolution of symptoms and has had no recurrence for the past 2 years.

This case was presented by Hanna Zembrzuska, MD, Patricia J. Papadopoulos, MD, William R. Gilliland, MD, and Mark D. Murphey, MD, at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or US government.

References:

REFERENCES

1. Toohey AK, LaSalle TL, Martinez S, Polisson RP. Iliopsoas bursitis: clinical features, radiographic findings, and disease associations. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1990;20:41-47.

2. Byrne PA, Rees JI, Williams BD. Iliopsoas bursitis-an unusual presentation of metastatic bone disease. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:285-288.

3. Johnston CA, Wiley JP, Lindsay DM, Wiseman DA. Iliopsoas bursitis and tendinitis: a review. Sports Med. 1998;25:271-283.

4. Kozlov DB, Sonin AH. Iliopsoas bursitis: diagnosis by MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:625-628.

5. Parziale JR, O’Donnell CJ, Sandman DN. Iliopsoas bursitis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:690-691.

6. Wunderbaldinger P, Bremer C, Schellenberger E, et al. Imaging features of iliopsoas bursitis. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:409-415.

7. Johnston CA, Lindsay DM, Wiley JP. Treatment of iliopsoas syndrome with a hip rotation strengthening program: a retrospective case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:218-224.

8. Adler RS, Buly R, Ambrose R, Sculco T. Diagnostic and therapeutic use of sonography-guided iliopsoas peritendinous injections. AJR. 2005;185:940-943.