Infrapatellar Pain in a Young Woman

A 23-year-old woman who reported experiencing direct trauma to her right knee on a hard surface 3 months earlier was admitted to the arthroscopy unit with complaints of decreased range of motion (flexion, 90°; extension, 75°) and intractable pain.

A 23-year-old woman who reported experiencing direct trauma to her right knee on a hard surface 3 months earlier was admitted to the arthroscopy unit with complaints of decreased range of motion (flexion, 90°; extension, 75°) and intractable pain. She also had swelling in the knee. Physical examination revealed the “bulge sign,” a synovial fluid wave with squeezing of the knee at the medial aspect characteristic of small effusions. The patellar tendon and femoral condyles were tender to palpation with the knee extended.

Ultrasonography showed mild effusion that was remarkable on quadriceps contraction. The sulcus angle and trochlear depth were normal.

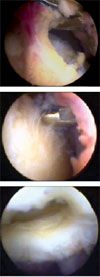

The patient underwent arthroscopy with resection of hypertrophic fat pad tissue in the infrapatellar area (photographs). A diagnosis was made with the arthroscopy. What does it show?

What is your diagnosis?

Find the answer on the next page.

The patient had a hypertrophic infrapatellar fat pad (Hoffa disease) and small medial plica; both were resected under arthroscopic control. Hoffa disease is an obscure but consistent cause of anterior knee pain that often is perceived as a rare condition. The diagnosis usually is made by exclusion.1

Hoffa disease was described in 1904 by Albert Hoffa, a German surgeon. The condition is characterized by pain in the infrapatellar and retropatellar areas that often is exacerbated by knee movement; it results from femorotibial impingement with an enlarged infrapatellar fat pad. The impingement mechanism eventually leads to cartilage damage (top and middle photographs, below). In addition, the infrapatellar fat pad is considered the source of several proinflammatory molecules in knee osteoarthritis.2

The prevalence of Hoffa disease is unknown. In a study by Kumar and associates,1 the condition was present as an isolated lesion in 1.3% of patients who underwent arthroscopy. They found an overall incidence of 6.8%.

Arthroscopy is an accurate tool for the diagnosis and definitive management of a hypertrophic fat pad. Direct observation of inflammation, fibrosis, and impingement is helpful in planning the amount of tissue to resect.

In a case series of 62 patients, von Engelhardt and colleagues3 concluded that MRI should be considered for the diagnosis of infrapatellar fat pad impingement. Edema of the Hoffa fat pad was the most important MRI criterion for identifying the impingement in this series.

Use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography is increasing in office practice. This imaging modality may be useful in the diagnosis of patellar tendinitis, infrapatellar bursitis, and jumper’s knee, all causes of infrapatellar pain that may mimic a hypertrophic fat pad. Patients with abnormal flattening of the trochlear groove have episodes of patellar dislocation and anterior knee pain. A normal trochlear depth and sulcus angle measured by ultrasonography ruled out patellar instability in this patient.

A hypertrophic mediopatellar plica may mimic or even be associated with Hoffa disease, as was the case in this patient. In my opinion, the relationship between Hoffa disease and the mediopatellar plica has physiopathological importance in 2 ways. One, the inflammation and fibrosis of the mediopatellar plica resulting from femoral condyle impingement may involve the infrapatellar fat pad. Although the infrapatellar fat pad is located centrally beneath the patellar tendon, it can appear to be joined medially as a continuous structure in the presence of the medial plica. Two, the presence of a hypertrophic medial plica may decrease the motion of the fat pad medially with an impingement mechanism. I agree with Saddik and coworkers4 that the precise relationship with Hoffa impingement is unclear.

Excluding a 2009 study by Brooker and colleagues,5 most publications about a hypertrophic infrapatellar fat pad have been case reports; therefore, a conservative treatment has not been standardized. Because pain and swelling are common clinical manifestations, analgesics, NSAIDs, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections are used frequently before arthroscopy is considered. Most patients improve symptomatically after arthroscopic resection of a hypertrophic fat pad, which usually is indicated if conservative therapeutic options, including physical therapy, are not successful.

The surgical technique performed in this case was similar to that described by Kumar and colleagues.1 I usually use high-portal arthroscopic resection, which allows for excellent triangulation with the surgical instruments and provides a panoramic view of the infrapatellar recess (bottom photograph, above). During the procedure, extension of the knee or pressure applied on the patellar tendon by an assistant often facilitates grasping of the fat pad tongue. This maneuver also provides a better idea about the size of the fat pad and avoids violation of the anterior capsule and injury of the patellar tendon.

A motorized shaver can be used to remove the hypertrophic fat pad. However, I prefer using a basket forceps placed through the anterolateral portal. After a complete release of the fat pad, the grasping forceps placed in the superomedial portal is pulled out with a gentle screw-like movement. Because fat is friable tissue that can be entrapped in the superomedial portal,6 I recommend reviewing it before finalizing the procedure.

Quadriceps strength and range of motion exercises made up the main physiotherapy program for this patient. One month after the surgical intervention, she was asymptomatic with complete recovery of range of motion.

References:

1. Kumar D, Alvand A, Beacon JP. Impingement of infrapatellar fat pad (Hoffa’s disease): results of high-portal arthroscopic resection. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1180-1186.e1.

2. Distel E, Cadoudal T, Durant S, et al. The infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis: an important source of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3374-3377.

3. von Engelhardt LV, Tokmakidis E, Lahner M, et al. Hoffa’s fat pad impingement treated arthroscopically: related findings on preoperative MRI in a case series of 62 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:1041-1051.

4. Saddik D, McNally EG, Richardson M. MRI of Hoffa’s fat pad. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:433-444.

5. Brooker B, Morris H, Brukner P, et al. The macroscopic arthroscopic anatomy of the infrapatellar fat pad. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:839-845.

6. González AC. Fat pad entrapment in suprapatellar pouch following previous arthroscopic resection of infrapatellar fat pad and medial plica: a rare complication. J Musculoskel Pain. 2001;9:95-98.