A Perfect Storm of Missteps Brought the Opioid Epidemic

In part 2, experts discuss how the public health crisis has reached a third decade, and what plans are to combat addiction problems.

It was like a perfectly running machine: there was a demand, a supply, and little to no obstacles between.

The drugs—oxycodone (OxyContin), diazepam (Valium), and so on—were more effective than anything physicians had seen for pain treatment. Insurers and developers saw a product that couldn’t be matched, and an opportunity to treat one of the greatest patient populations in the world.

Patients felt better. Doctors felt good about their work, and profits were soaring. Nothing stopped the machine.

“The expectation was that you're going to get these drugs from a doctor, so drug companies were pushing it, doctors were writing [prescriptions], patients were demanding it, pharmaceutical companies were selling it, and it's all financed by health insurance,” Richard D. Blondell, MD, told HCPLive®.

The federal agencies responsible for regulation, Blondell said, were asleep at the wheel.

Nothing about what generated the opioid crisis was surprising. People discovered the very potent high from these very accessible drugs, and very few of the involved clinical parties were diligent to this issue. Even fewer were able to drive the national crisis; Blondell estimates 1% of physicians were prescribing 50% of the opioid doses. Only developers know who.

These companies kept researching and developing more powerful, potent, and addictive drugs. At some point, everyone involved was caught on to the big problem, but still, no one broke line.

“[Physicians] kind of knew it was wrong, but it's just easier to write a prescription than it was to talk to patients,” Blondell, professor emeritus of Family Medicine at the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University of Buffalo said. “And patients came to expect the doctors are going to relieve their pain.”

By the time the collective industrial conscience opted to put a stop to some of the irresponsible practices, it was too late, and addiction was spreading throughout the country. It had no limit on demographic—gender, age, location, income.

Prescription practices and laws began to constrict on the flow of prescriptions, but it was too late. Droves of addicted patients simply turned to heroin, and then to synthetic narcotics like fentanyl. The history of the opioid epidemic remains possibly the most complicated and multifaceted crisis in American history.

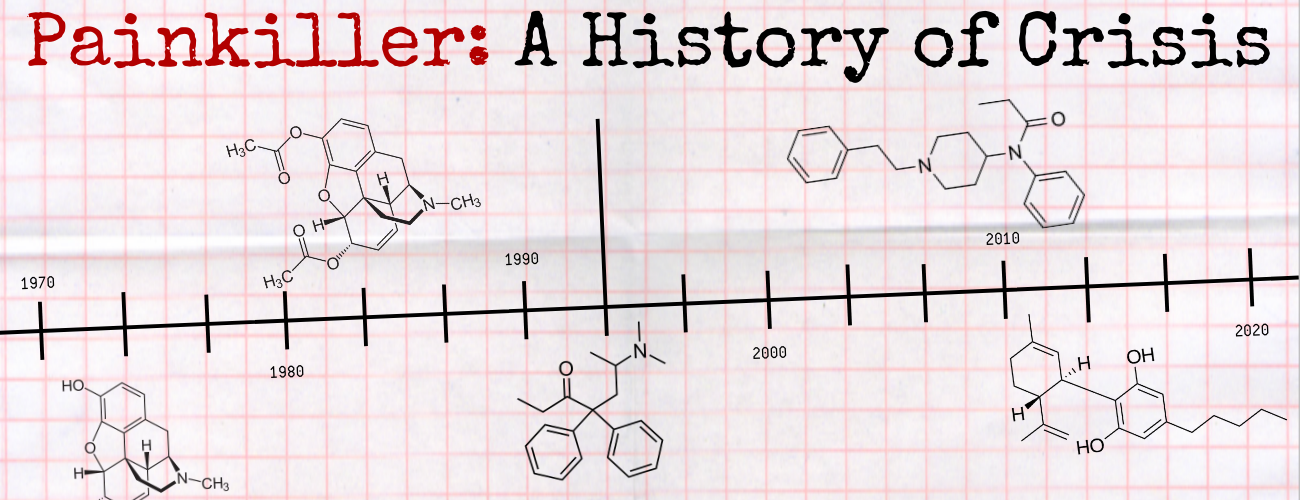

The Origins of the Painkiller Culture

Blondell explained painkiller culture began in the 1950s when doctors began to treat pain more, and the level of physician education was close to zero. During this time opioids were prescribed for cancer pain. Before long, it began to be prescribed for chronic pain, then eventually landing on treatment for virtually any type of pain.

But the true prelude of the opioid epidemic can be traced back to the late 1980s when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved morphine sulfate (MS Contin) in 1987, representing the first formulation of an opioid pain medicine that allowed dosing every 12 hours, as opposed to its predecessors which topped out at 4-6 hours.

Three years later, the FDA approved the fentanyl transdermal system (Duragesic), the first formulation of an opioid pain medicine in a three-day patch. Another 5 years later, they approved OxyContin, the first 12-hour release of oxycodone.

Everything from clinical endorsement to Oxycontin’s original slogan hung on its value as a longer-duration painkiller: “The One to Start With, and the One to Stay With.”

It didn’t take long into its life on the market for OxyContin to become an abused drug, Daniel Alford, MD, professor of Medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, told HCPLive. Patients soon realized they could crush the tablets and disrupt the slow release, achieving a chemical high.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has described the epidemic as a three-wave crisis. The first wave started as the prescription drug overdose rate rose steadily between 1999-2010, proceeding the marketing of these major drugs.

Heroin abuse, in relation to the improved regulation of opioids, began in 2010. The synthetic opioid crisis, the third wave, began shortly after that, when drug dealers found products like fentanyl were easier to manufacturer and transport than heroin.

The epidemic reached its peak burden on the US population in 2017, when more than 70,000 people overdosed. In 2018, still 68,000 overdosed.

It’s only with hindsight that experts discuss how tighter initial regulations on the production, promotion, and sale of opioids could have limited the damage that would take 20 years to play out on the country.

The Nature of Pain

Poor education on both the physician and patient standpoint can be attributed to the complex and unquantifiable nature of pain.

While most every other disorder and condition in medicine has a quantifiable target, pain is mainly based on the individual. Some patients can handle what becomes unbearable pain for others—all the while doctors can’t know exactly what the patient needs.

“As opposed to other vital signs like blood pressure and heart rate, where we have objective measures pain is very subjective,” Alford explained. “What does the 8 mean on a 10-point scale, or a 7? It's very individual and hard to interpret.”

Gerald Maguire, MD, the chair of psychiatry and neuroscience at the University of California Riverside School of Medicine, told HCPLive a legislative mandate is one of the leading factors for the epidemic.

In 2001, the California legislature passed AB-487, a bill that required every physician to complete a mandatory continuing education course on pain management within 5 years.

Maguire explained the bill was created without the input from medical boards and resulted in doctors being encouraged to prescribe more opioids to treat pain.

With the individual nature of pain, coupled with a poor understanding from physicians and a push in the 1990s to prescribe opioids to treat virtually any type of pain, it was no surprise the epidemic spread as quickly as it did.

Americans also faced a common issue in public health crises: health illiteracy. Their knowledge of pain care and symptom management was ill-informed, and the common perception was that physicians were in fact undertreating pain. They at least knew drugs were available to take the pain away.

It seems, over time, some of the safeguards that prevented prescription abuse slowly dissolved. Blondell pointed to the pharmacist’s role in challenging questionable prescriptions from doctors. And again, insurance companies were well aware that an extremely small percentage of doctors were prescribing the majority of the opioids.

But these safeguards were not used to their fullest extent, while addiction pharmacotherapy has faced the full brunt of clinical scrutiny.

“Insurance companies know who is prescribing all the drugs,” Blondell said. “The irony is there was no control over getting people addicted, but once they were addicted, there are all kinds of hurdles that you had to jump through to treat them, which was just kind of crazy.”

Hope for the Future

Just as the blame for the opioid epidemic goes across the spectrum of the healthcare industry, the eventual solution must also involve those same industries working to improve addiction and prescription practices. The machine has to run for the betterment of the field it helped nearly destroy.

Blondell estimates it will be at least 20 years before a meaningful dent is made in the epidemic, partially because younger people who are currently addicted will likely be dealing with these issues for the remainder of their lives.

But there is optimism for the future, as fewer and fewer patients are starting opioids, and doctors are opting for alternatives to treat pain. Also, naloxone (Narcan) has become a popular tool for emergency responders and police officers to at least limit the rate of overdoses.

Another reason for hope is the recent creation of addiction treatment as a specialty. The next generation of doctors can choose to treat all the generations afflicted by this epidemic.

“So, the bottom line is we can treat chronic pain without opiates,” Blondell said. “It's involved, it's time and labor-intensive and expensive, but we can do it.”