Steps to Take in Managing Metatarsalgia

Familiarity with metatarsalgia, an array of disorders that cause pain to the forefoot, enhances the clinician's ability to make the proper diagnosis.

ABSTRACT: Familiarity with metatarsalgia, an array of disorders that cause pain to the forefoot, enhances the clinician's ability to make the proper diagnosis. Making a correct diagnosis and gaining an understanding of the factors causing the problems are the first steps toward developing a successful treatment plan. Forefoot problems revolve around the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. Patients complain of pain in the forefoot in the area of the lesser metatarsal heads. Morton neuroma is perhaps the most common cause. Corns often are overlooked on physical examination. Perhaps the easiest way to differentiate stress injuries from other causes of metatarsal pain is to identify the specific location of the pain and swelling. Instability of the MTP joint is a common injury that until recently was poorly understood. (J Musculoskel Med. 2011;28:346-351)

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Metatarsalgia constitutes an array of disorders that cause pain to the forefoot. The term describes metatarsal pain but not the cause of this symptom. Determining the underlying cause can be remarkably difficult, but it is key to treatment success.

Much about the causes of metatarsalgia remains unknown. However, recent studies have led to considerable insight into the underlying pathophysiology. Effective treatment programs are available, and more are likely to be developed in the coming years. In this article, I review the relevant anatomy, clinical presentation and physical examination, and a few of the more common causes and approaches to treatment.

ANATOMY

Problems with the forefoot revolve around the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint (Figure 1). The lesser toes arise from the metatarsal bones, which extend from the arch to the weight-bearing surface of the forefoot. The metatarsal head articulates with the proximal phalanx to create the MTP joint.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1 – The lesser toes arise from the metatarsal bones, which extend from the arch to the weight-bearing surface of the forefoot. The metatarsal head articulates with the proximal phalanx to create the metatarsophalangeal joint, where forefoot problems (metatarsalgia) develop. This joint is supported by the plantar plate. The flexor digitorum longus and flexor digitorum brevis tendons travel through a groove in the bottom of the metatarsal head and attach to the base of the distal and middle phalanges, respectively. The extensor hood envelops the dorsal portion of the toe.

This joint is supported by the plantar plate, a rectangular fibrocartilaginous ligament that attaches the inferior metatarsal neck to the plantar aspect of the base of the proximal phalanx. This ligament determines the static posture of the toe and transfers body weight from the metatarsal heads to the floor. Collateral ligaments support the medial and lateral sides of the joint. The plantar subcutaneous adipose tissue absorbs and disperses body weight as it is transferred to the floor.

Interdigital nerves and vascular structures pass along either side of the metatarsal head, plantar to the transverse metatarsal ligament, which connects the adjacent metatarsal heads. Then, as the interdigital nerve travels into the toes, it divides into branches that supply sensation to opposing surfaces of each toe web.

As in the hand, 2 flexor tendons-the flexor digitorum longus and flexor digitorum brevis-travel through a groove in the bottom of the metatarsal head and attach to the base of the distal and middle phalanges, respectively. The extensor hood envelops the dorsal portion of the toe; its origins include the interosseous and lumbrical intrinsic muscles and the extensor digitorum longus and extensor digitorum brevis tendons. The extensor hood then attaches to the dorsal base of the middle and distal phalanges.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

By definition, patients with metatarsalgia complain of pain in the forefoot in the area of the lesser metatarsal heads. The anatomy of the hallux is unique; therefore, the problems of this toe usually are considered separately.

The pain can involve 1 or more of the lesser metatarsal heads, and a variable degree of swelling or callusing may be present. The incidence of deformity of the lesser toes in the general population is reported to be 2% to 20%.1 The presence of these deformities often is associated with pain, and the prevalence of both pain and deformity in the forefoot increases considerably with advancing age.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Evaluation of the skin, including the toe web spaces, discloses the presence of any corns or calluses, providing many clues to abnormal ways in which the foot distributes weight. The stability of the ligaments that support the forefoot joints should be evaluated; the dorsal drawer, or mini-Lachman, test assesses the integrity of the plantar plate of the toe at the MTP joint (Figure 2).2

FIGURE 2

Figure 2 – The dorsal drawer, or mini-Lachman, test assesses the integrity of the plantar plate of the toe at the metatarsophalangeal joint. Normally mild translation is appreciated when the plantar plate is intact (A). If the plantar plate is torn or attenuated, a reducible dislocation of the joint is possible with mild force (B).

Localized swelling in the soft tissues and around the bones may be very helpful in identifying the injured structure. Sensory testing may reveal a systemic or local neuropathy. Squeezing the metatarsal heads together may result in a clicking (the Mulder sign), which may signify an interdigital mass, such as a neuroma or bursa. The degree of flexibility and the posture of the foot and ankle may reveal abnormalities that may lead to nonuniform weight distribution on the foot.

Because the causes of metatarsalgia often revolve around problems that lead to increased forefoot pressure and the causes may be remote from the foot, a detailed physical examination of the leg and back is necessary. Knee arthritis and hamstring contractures may limit knee extension, thus shifting weight onto the forefoot.3 Other contributors to exaggerated forefoot pressure include obesity,4 especially abdominal obesity; pregnancy5; and advanced age.6 Other areas of joint involvement may provide clues to systemic problems with synovitis, such as rheumatoid arthritis and gout.

CAUSES AND TREATMENT

Morton neuroma

Metatarsalgia has several potential causes (Table), and some of these processes may coexist. Morton neuroma, an irritation of the interdigital nerve as it passes from the forefoot into the toes, is perhaps the most common and well known. Although there are several theories on the causes of this form of neuritis, they are not well understood.

TABLE

Differential diagnosis of metatarsalgia

Usually only 1 nerve is affected. The region in which Morton neuroma occurs most frequently is the third interdigital nerve, followed by the second. The disorder is differentiated from other causes of metatarsalgia by the location (within the interspaces, between the metatarsal heads) and the presence of sensory disturbances, detected on examination or with the history taking.

Treatment of patients with Morton neuroma begins with relief of weight on the forefoot. Support of the metatarsal heads through the use of a metatarsal pad or orthosis is a reasonable approach, but little evidence of effectiveness is available. Off-loading of the area with a commercially available rocker-soled shoe with a toe box that does not restrict the metatarsal heads should be tried.

Injection with corticosteroids or sclerosing agents, such as alcohol and phenol, often is recommended. Corticosteroid injections have been shown to be effective in the short and medium term,7,8 although they are not uniformly curative. Good results have been reported with sclerosing injections, with minimal complications.9,10 However, severe neuritis has been seen (personal observation), and it is a difficult-to-manage complication.

Nerve excision is the traditional surgical approach to treatment. Pathological examination of the specimens generally shows intraneural fibrosis.11 Release of the nerve through incision of the transverse metatarsal ligament has been shown to be as effective as surgical release; recovery is improved, and difficulty with nerve irritation and numbness is lessened.

Corns

These are calluses that grow into the subcutaneous tissue as a result of constant pressure. They often are overlooked on physical examination, but once they are discovered, treatment is rather simple.

Hard corns develop between the foot and an external source of pressure, such as a shoe or the ground. Hard corns may be differentiated from warts clinically by their size (corns are about 3 to 5 mm in diameter and warts may range from 2 to 20 mm) and a lack of perforating blood vessels into the lesion (in warts, they appear as blackish spots within the keratin).

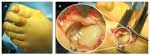

FIGURE 3

Figure 3 – A soft corn in the fourth toe web is shown (arrow). Hyperkeratotic skin debris has displaced the normal subcutaneous tissue between the lateral base of the fourth proximal phalanx and metatarsal heal and the medial condyle of the distal portion of the fifth proximal phalanx.

Soft corns develop in response to pressure generated by 2 opposing bony prominences (Figure 3). The pressure stimulates hypertrophic epidermal growth that, because of the pressure, does not exfoliate. As a result, the mass of retained debris focally thickens the epidermis, displacing the underlying protective subcutaneous tissue. Ulceration and abscess formation may occur.

Management of corns centers around local pressure relief. The most direct method is paring of the lesion. Unlike other varieties of scalpel blades, the #17 has its cutting blade on the distal edge, allowing the physician to sweep across the lesion parallel to the skin in fine, controlled, superficial strokes, preventing inadvertent penetration into the deeper, vascular layers. The paring should be discontinued when the hard callus is removed or the layers of skin around the lesion thin so that the pinkish dermal tissue becomes visible.

Over several days, the deeper part of the corn often becomes superficial as the subcutaneous tissue returns to its normal position, allowing for further removal. Repeated paring or abrasion with a pumice stone or other instrument should be continued until the lesion has been removed.

Patients who have soft corns should be advised to switch to footwear that has adequate room in the toe box. Toe spreaders help separate phalangeal bones that may be pressing on one another. Rocker-soled shoes and orthoses help disperse pressure away from hard corns on the plantar surface of the forefoot and, along with continued paring or abrasion, lead to elimination of the lesion.

In cases that are resistant to treatment, surgical excision of a prominent exostosis or elevation of the metatarsal head may be curative. However, excessive resection may lead to joint instability or transfer of the lesion to an adjacent metatarsal head.

Metatarsal stress fractures

Stress injuries are caused by repeated pressure that overloads the body's ability to repair itself and fatigues the bone, unlike traumatic fractures, which are caused by a single blow that exceeds the strength of the bone. Microinjury accumulates within the bone and eventually results in complete mechanical failure. The metatarsals are the bones most prone to stress injury.

Patients with metatarsal stress fractures present to the clinician with swelling and pain in the forefoot. The pain worsens with walking, especially walking without shoes or on uneven surfaces.

Perhaps the easiest way to differentiate stress injuries from other causes of metatarsal pain is to identify the specific location of the pain and swelling along a segment of the metatarsal shaft or neck. Usually, there also is a firm enlargement of this painful area. The results of radiography (Figure 4) often are negative for the first several weeks after the onset of symptoms.

FIGURE 4

Figure 4 – This x-ray film shows stress fractures of the second and third metatarsals (arrows). Identifying the specific location of the pain and swelling along a segment of the metatarsal shaft or neck may be the easiest way to differentiate stress injuries from other causes of metatarsal pain.

Mechanical protection of the area is the primary form of treatment. Required protection may range from commercial protective footwear, such as a rocker-soled shoe, to the use of a cast or cast boot, depending on the amount of pain and the activity needed to aggravate it. Continuing weight bearing on the extremity during recuperation usually is possible. Periodic monitoring of injury alignment and healing progress with radiographs is suggested. Symptoms generally improve over 1 to 3 months. Surgery is necessary only rarely to realign the metatarsal head or when the injury does not unite.

Metatarsophalangeal

instability

Instability of the MTP joint is a common problem that until recently was poorly understood. Many older patients show the various forms of hammertoe that usually result from previous MTP instability. Often, there is a period of swelling and pain immediately before the development of these deformities.

MTP synovitis is heralded by sudden pain and swelling around 1 or more MTP joints. Usually, no inciting injury is recalled. The tenderness is at the top of the joint and often near the plantar base of the proximal phalanx. Increased laxity to dorsal drawer stress of the MTP joint is common.

Lesser toe deformity often is found coincident to or after MTP synovitis (Figure 5), and the patient should be counseled about this potential development. However, there is no effective treatment.

FIGURE 5

Figure 5 – Shown is the foot of a patient who has second metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint synovitis with dorsiflexion and medial deviation deformity of the MTP joint (A). This intraoperative photograph (B) shows a tear (arrows) in the lateral attachment of the plantar plate to the plantar base of the proximal phalanx.

Disruption of the plantar plate of the MTP joint is a common surgical finding. The disruption changes the posture of the MTP joint so that it extends to varying degrees (see Figure 5). Incomplete rupture of the plantar plate causes the toe to deviate into valgus or varus. The extended posture of the MTP joint changes the tension in the flexor (tightening) and extensor (loosening) tendons, resulting in the characteristic posture of the interphalangeal joints.

The supporting structures of the flexor tendons on the bottom of the metatarsal head may become unstable, allowing the tendons to subluxate to the side of the metatarsal head. The leverage of the flexor tendon on the MTP joint changes drastically so that it becomes less effective in flexing the joint. As a result, the tension within the flexor tendon causes the toe to deviate to the side rather than flex the MTP joint, resulting in the crossover toe deformity. This shift in toe position can develop rather suddenly.

Nonoperative treatment, starting with removing the load from the painful and tender joint, is effective.12 An over-the-counter arch support and a rocker-soled shoe can reduce forefoot load and decrease pain appreciably. Posture and flexibility exercises that focus on the hamstrings, Achilles tendon, and plantar fascia also reduce forefoot load.

NSAIDs reduce pain, but their effect on the underlying pathophysiology is unclear. Injection of corticosteroids into the joint may provide considerable relief, but the effect of corticosteroids on long-term outcome is unknown. Some authors have suggested that corticosteroids may increase the likelihood of deformity because of their documented inhibitory effect on the metabolism of tendon and cartilage cells.13

Multiple methods of surgical repair have been described. Most involve the transfer of local tendons, such as the flexor digitorum longus14 and extensor digitorum brevis,15 in an effort to reconstruct the stability of the plantar plate. The reported success rates of these procedures have varied; the incidences of recurrence, stiffness, and persistent pain have been significant. Methods were introduced recently to directly repair the plantar plate, and the initial results have been encouraging.16 Whether these techniques will be an improvement over the more traditional methods is unclear.

SUMMARY

Increased familiarity with the underlying causes of metatarsalgia and the various disorders helps in making the diagnosis. Then, effective nonoperative and operative options can be discussed and implemented.

Comments about/problems with this article? Sendfeedback.

References:

References

1. Caselli MA, George DH. Foot deformities: biomechanical and pathomechanical changes associated with aging, part 1. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2003;20: 487-509, ix.

2. Espinosa N, Brodsky JW, Maceira E. Metatarsalgia. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:474-485.

3. Harty J, Soffe K, O'Toole G, Stephens MM. The role of hamstring tightness in plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:1089-1092.

4. Hills AP, Hennig EM, McDonald M, Bar-Or O. Plantar pressure differences between obese and non-obese adults: a biomechanical analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1674-1679.

5. Karadag-Saygi E, Unlu-Ozkan F, Basgul A. Plantar pressure and foot pain in the last trimester of pregnancy. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31:153-157.

6. Mickle KJ, Munro BJ, Lord SR, et al. Foot pain, plantar pressures, and falls in older people: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1936-1940.

7. Bennett GL, Graham CE, Mauldin DM. Morton's interdigital neuroma: a comprehensive treatment protocol. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:760-763.

8. Rasmussen MR, Kitaoka HB, Patzer GL. Nonoperative treatment of plantar interdigital neuroma with a single corticosteroid injection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;326:188-193.

9. Magnan B, Marangon A, Frigo A, Bartolozzi P. Local phenol injection in the treatment of interdigital neuritis of the foot (Morton's neuroma). Chir Organi Mov. 2005;90:371-377.

10. Fanucci E, Masala S, Fabiano S, et al. Treatment of intermetatarsal Morton's neuroma with alcohol injection under US guide: 10-month follow-up. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:514-518.

11. Giannini S, Bacchini P, Ceccarelli F, Vannini F. Interdigital neuroma: clinical examination and histopathologic results in 63 cases treated with excision. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:79-84.

12. Trepman E, Yeo SJ. Nonoperative treatment of metatarsophalangeal joint synovitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:771-777.

13. Scutt N, Rolf CG, Scutt A. Glucocorticoids inhibit tenocyte proliferation and tendon progenitor cell recruitment. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:173-182.

14. Myerson MS, Jung HG. The role of toe flexor-to-extensor transfer in correcting metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the second toe. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:675-679.

15. Lui TH. Correction of crossover deformity of second toe by combined plantar plate tenodesis and extensor digitorum brevis transfer: a minimally invasive approach. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011 Mar 9; [Epub ahead of print].

16. Weil L Jr, Sung W, Weil LS Sr, Malinoski K. Anatomic plantar plate repair using the weil metatarsal osteotomy approach. Foot Ankle Spec. 2011;4:145-150.