Article

The Importance of Phenotype Testing in Severe Asthma

Advertorial content funded and developed by GSK.

Dr. Ledford is a paid consultant to GSK.

Background

Asthma is a disease of the lungs characterized by chronic airway inflammation and fluctuating airflow limitation.1 It is associated with wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing at night or the early morning.2 Approximately 25 million people in the United States have asthma, with over 8% of adults and nearly 6% of children affected by this common condition.1,3

When a person’s asthma requires use of high-dose corticosteroid inhalers or oral steroids to prevent it from being uncontrolled, or it remains uncontrolled despite these medicines, it is referred to as severe asthma.4 Severe asthma involves recurrent exacerbations, reduced lung function, and worsening asthma control.1,5 Up to 10% of the asthma population has severe or refractory disease, which accounts for disproportionately high health care costs due to suboptimal treatment responses and worsening symptoms.6-8 Additionally, increased asthma severity and poorer disease control are independent predictors of death.9

Although the complete pathophysiology of asthma has yet to be elucidated, numerous genetic, environmental, and work-related factors contribute to its development.2 Similarly, asthma is a heterogenous disease associated with several clinical phenotypes differentiated by natural history, severity, and response to therapy.10 Phenotypes of severe asthma include allergic asthma, neutrophilic asthma,eosinophilic asthma, and obesity-related asthma.10

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are a mainstay of asthma treatment, but even high-dose ICS may not offer sufficient control of severe asthma due to underlying factors.1 Oral corticosteroids (OCS) may be necessary when patients fail to respond to current therapy, experience worsening symptoms, or have exacerbations requiring hospitalization or emergency department visits.1 However, these therapies are associated with serious adverse effects, including psychiatric conditions and disorders of the adrenal glands; the eyes; and the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, metabolic, and gastrointestinal systems.11

Early testing, targeted therapy initiation, and reduced corticosteroid use may be particularly important for younger patients who face a potential lifetime of asthma management. In this article, Dennis K. Ledford, MD, professor of Medicine and Pediatrics and Ellsworth & Mabel Simmons Professor of Allergy and Immunology at the Morsani College of Medicine of the University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida, and Section Chief of Allergy/Immunology at the James A Haley VA Hospital, shares his clinical perspective on severe asthma with an eosinophil phenotype. In particular, he discusses the importance of testing blood eosinophil count during initial disease assessment to personalize therapy selection and reduce corticosteroid use, and he describes effective treatment strategies.

Assessing for the Eosinophilic Phenotype in Severe Asthma

Eosinophils are present in the large airway tissue of up to approximately half to two-thirds of patients with severe asthma.5 Eosinophils are involved in the type 2 immune response, which is associated with severe asthma; this encompasses activation of numerous cell types, including T-helper type 2 (Th2) and innate lymphoid type 2 (ILC2) cells. Exposure to allergens activates Th2 and produces cytokines (interleukin [IL]-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13), resulting in production of immunoglobulin (Ig) E, increased levels of eosinophils, and activation of mast cells. A nonallergic response can also occur in people with severe asthma; it is characterized by the activation of ILC2 cells and the generation of IL-5 and IL-13.12,13 Regardless of the pathway, IL-5 is the primary cytokine that drives eosinophil growth, differentiation, recruitment, activation, and survival.12,13

As compared to other types of asthma, severe asthma with the presence of eosinophils involves worse asthma symptoms, a lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and a greater risk for exacerbations and near-death events.5 The International Severe Asthma Registry reported that 74% to 84% of patients with severe asthma most likely had eosinophilic asthma.14* Dr Ledford confirmed, “Individuals who tend to exacerbate the most tend to be eosinophilic.” In patients with severe asthma, regardless of their use of high corticosteroid doses, persistently high levels of eosinophils are more common among individuals with late-onset disease than those with early-onset disease.5 He continued, “If you look at severe eosinophilic asthma, most of those patients seem to start as young adults, and they tend to get a bit worse through their 30s and 40s, then, sometimes, it persists on through life.”

*84% of adults identified as “most likely” to have an eosinophilic phenotype in prospective analysis (N = 1716) using a predefined algorithm of ≥ 1: blood eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells/μL; on anti-IL-5/5R therapy; blood EOS count of ≥ 150-300 cells/μL on maintenance OCS or ≥ 2: nasal polyps, elevated FeNO, late-onset asthma. 74% identified in retrospective analysis of medical records in the United States (n = 1891).14

Asthma Report Recommendations

Assessment of risk factors for poor outcomes in asthma is important during the diagnostic process and periodically throughout the disease course.1 The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) report states that the presence of type 2 inflammatory markers, such as higher blood eosinophils, are associated with increased risk of asthma exacerbations.1 In patients receiving high-dose ICS or maintenance OCS, markers of type 2 inflammation include a blood eosinophil level of at least 150 cells/μL, a fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) level of at least 20 ppb, a sputum eosinophil count of at least 2%, and/or asthma that is clinically triggered by allergens.1 To confirm that the asthma does not involve type 2 inflammation, these patients should have their blood eosinophil and FeNO levels checked up to 3 different times, such as when their asthma worsens, before they receive an OCS, or either after their OCS or on their lowest possible dose.1

Ledford indicated, “Biomarkers can help us categorize asthma, and they include the presence of allergy, the eosinophil count in the blood, and, sometimes, measuring FeNO from in-office testing. So, with all that information coupled with family history and personal history and current medication use, I can come to a conclusion that it is severe asthma.”

Identifying Patients Who Most Likely Have Eosinophilic Asthma

According to Dr Ledford,“Elevated blood eosinophil counts are so common that I would not hesitate to check a count if an asthma patient was having trouble.” He would also suspect severe eosinophilic asthma in patients who do not experience an adequate response to their maintenance inhalers. He cautioned that hospitalization is not a required defining factor—major interruptions in work and sleep may also suggest this phenotype.

Ledford stated, “There's no real way an individual could tell that they have eosinophilic asthma vs noneosinophilic asthma, other than if their blood eosinophil count is measured. Asthma that's noneosinophilic behaves in a way very similar to that of asthma that's eosinophilic. The big difference is the odds of having severe disease and having exacerbations.” He continued, “Another marker that would make me strongly suspect eosinophilic disease is a coexistence of sinus problems with polyps and asthma.”

Recommended Treatment Approach for Severe Eosinophilic Asthma

“Prednisone or cortisone-like medicines really affect eosinophil biology,” noted Dr. Ledford. “Giving prednisone or systemic steroids to a patient with eosinophilic asthma makes them much better. The problem is that there’s a cumulative adverse effect burden. There are acute effects—patients feel nervous and can’t sleep. These chronic effects such as thinning of the bone, increased risk of cardiovascular problems and weight gain are things that really affect patients' health."

Type 2 inflammation in severe asthma can be unresponsive to high doses of ICS.1 If patients with severe asthma experience exacerbations or suboptimal symptom management despite use of high-dose ICS in combination with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA), phenotypic assessment and referral to a specialist are recommended. Depending on their findings, asthma biologics may be recommended.1

NUCALA (mepolizumab) Injection 100 mg/mL

Per GINA, asthma biologics, such as NUCALA, are recommended for patients with severe eosinophilic asthma who have experienced exacerbations within the past year and who have blood eosinophil levels of at least 150 cells/μL on recent bloodwork.1

NUCALA is an IL-5 antagonist monoclonal antibody (IgG1κ) indicated for the add-on maintenance treatment of adult and pediatric patients aged 6 years and older with severe asthma and with an eosinophilic phenotype. NUCALA is not indicated for the relief of acute bronchospasm or status asthmaticus. Predictors of anti-IL5 therapy efficacy include higher blood eosinophil levels, more exacerbations than in the previous year, onset of asthma in adulthood, and nasal polyposis.1

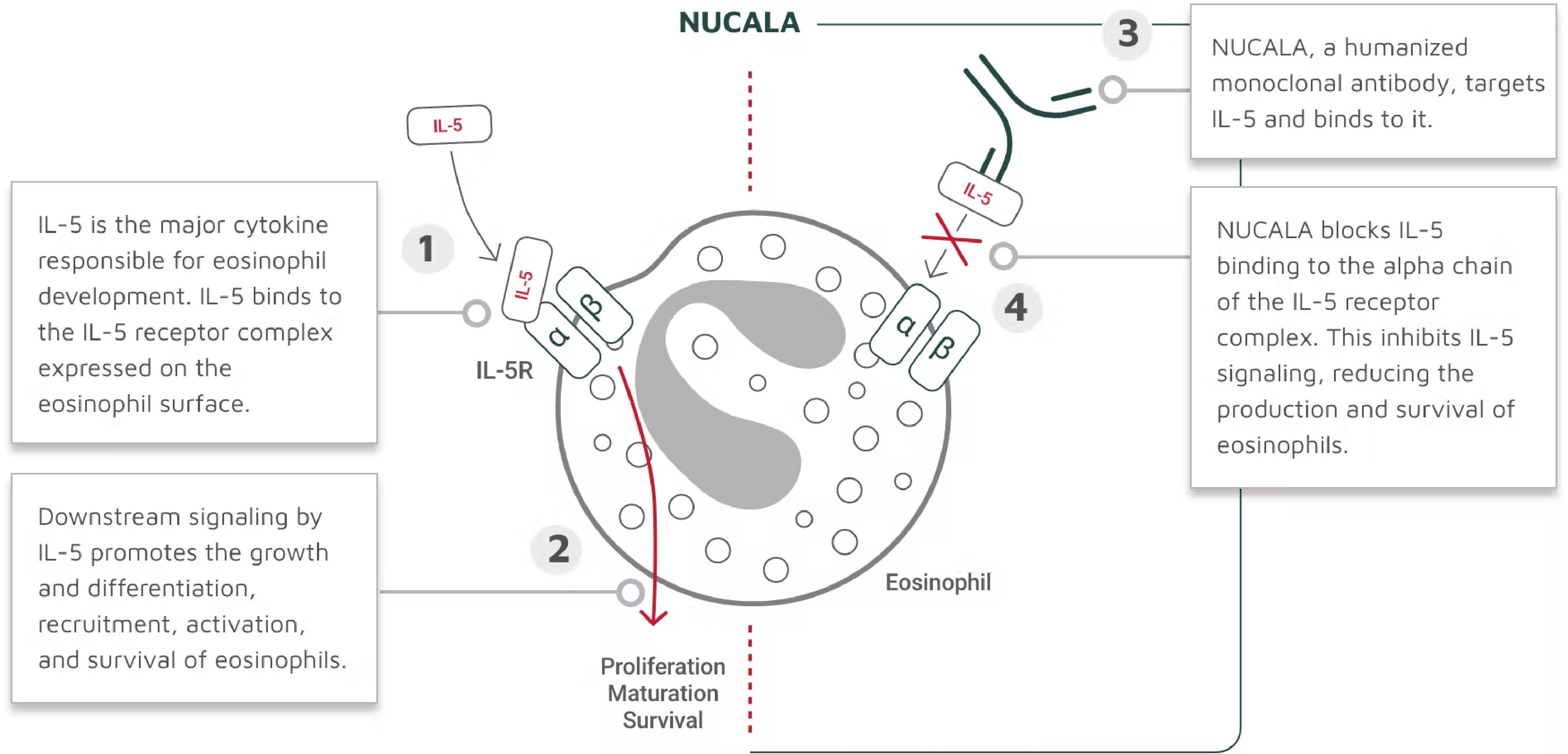

NUCALA targets and binds to IL-5, thus inhibiting IL-5 signaling and reducing the production and survival of eosinophils (Figure). The mechanism of action of NUCALA in asthma has not been definitively established.15

Figure. How Nucala Works15,a

a The mechanism of action of mepolizumab in asthma has not been definitively established.

“NUCALA targets eosinophils and reduces the cells’ activity, but it doesn't eliminate the cells. We think that could be beneficial,” Dr Ledford explained. He acknowledged, “In the majority of patients with allergies who have asthma, severe nonallergen triggers often contribute to the asthma exacerbations. NUCALA also has numerous clinical trials that evaluated reduction in exacerbations, OCS use, and other important measures in severe eosinophilic asthma.”

Important Safety Information

CONTRAINDICATIONS

NUCALA should not be administered to patients with a history of hypersensitivity to mepolizumab or excipients in the formulation.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity reactions (eg, anaphylaxis, angioedema, bronchospasm, hypotension, urticaria, rash) have occurred with NUCALA. These reactions generally occur within hours of administration but can have a delayed onset (ie, days). If a hypersensitivity reaction occurs, discontinue NUCALA.

Acute Asthma Symptoms or Deteriorating Disease

NUCALA should not be used to treat acute asthma symptoms, acute exacerbations, or acute bronchospasm.

Opportunistic Infections: Herpes Zoster

In controlled clinical trials, 2 serious adverse reactions of herpes zoster occurred with NUCALA compared to none with placebo. Consider vaccination if medically appropriate.

Reduction of Corticosteroid Dosage

Do not discontinue systemic or inhaled corticosteroids abruptly upon initiation of therapy with NUCALA. Decreases in corticosteroid doses, if appropriate, should be gradual and under the direct supervision of a physician. Reduction in corticosteroid dose may be associated with systemic withdrawal symptoms and/or unmask conditions previously suppressed by systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Parasitic (Helminth) Infection

Treat patients with pre-existing helminth infections before initiating therapy with NUCALA. If patients become infected while receiving NUCALA and do not respond to anti-helminth treatment, discontinue NUCALA until infection resolves.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

In clinical trials in patients receiving NUCALA, the most common adverse reactions (≥5%) were headache, injection site reaction, back pain, and fatigue. Systemic reactions, including hypersensitivity, also occurred. Manifestations included rash, pruritus, headache, myalgia, and flushing; the majority were experienced the day of dosing.

USE IN SPECIFIC POPULATIONS

A pregnancy exposure registry monitors pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to NUCALA during pregnancy. To enroll call 1-877-311-8972 or visit http://www.mothertobaby.org/asthma.

The data on pregnancy exposures are insufficient to inform on drug-associated risk. Monoclonal antibodies, such as mepolizumab, are transported across the placenta in a linear fashion as the pregnancy progresses; therefore, potential effects on a fetus are likely to be greater during the second and third trimesters.

Please see full Prescribing Information and Patient Information for NUCALA.

Conclusions

When testing severe asthma patients for potential biomarkers, clinicians should test for eosinophils multiple times before ruling out severe eosinophilic asthma. Identifying elevated levels of eosinophils in patients soon after a diagnosis of severe asthma can help guide targeted treatment selection, and it may be particularly helpful in treating patients with severe disease that has been refractory to standard therapies.1 We hope to have more data on long-term outcomes and real-world data with asthma biologics to guide asthma management. “If you have therapeutics that can help make a difference, like NUCALA, you should explore those options,” Dr Ledford stated. “Patients with severe eosinophilic asthma have lived with it, sometimes, for decades. They just think that it's normal, and they accept it. And it's unfortunate, because we have so many good therapeutic options now.”

Advertorial intended for US healthcare professionals only.

Trademarks are owned by or licensed to the GSK group of companies.

©2022 GSK or licensor.

MPLADVR220002 October 2022

Produced in USA.

References

1. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2022. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2022. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-05-03-WMS.pdf

2. Learn how to control asthma. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed July 1, 2021. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/faqs.htm

3. Most recent national asthma data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed May 25, 2022. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm

4. Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343-73. doi:10.1183/09031936.00202013

5. Wenzel S. Severe asthma in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(2):149-160. doi:10.1164/rccm.200409-1181PP

6. Antonicelli L, Bucca C, Neri M, et al. Asthma severity and medical resource utilisation. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(5):723-729. doi:10.1183/09031936.04.00004904

7. Lane S, Molina J, Plusa T. An international observational prospective study to determine the cost of asthma exacerbations (COAX). Respir Med. 2006;100(3):434-450. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2005.06.012

8. Cisternas MG, Blanc PD, Yen IH, et al. A comprehensive study of the direct and indirect costs of adult asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(6):1212-1218. doi:10.1067/mai.2003.1449

9. Omachi TA, Iribarren C, Sarkar U, et al. Risk factors for death in adults with severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(2):130-136. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60200-1

10. Wenzel S. Severe asthma: from characteristics to phenotypes to endotypes. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(5):650-658. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03929.x

11. Volmer T, Effenberger T, Trautner C, Buhl R. Consequences of long-term oral corticosteroid therapy and its side-effects in severe asthma in adults: a focused review of the impact data in the literature. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(4):1800703. doi:10.1183/13993003.00703-2018

12. Naik SR, Wala SM. Inflammation, allergy and asthma, complex immune origin diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic agents. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2013;7(1):62-95.

13. Park YM, Bochner BS. Eosinophil survival and apoptosis in health and disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(2):87-101. doi:10.4168/aair.2010.2.2.87

14. Heaney LG, Perez de Llano L, Al-Ahmad M, et al. Eosinophilic and Noneosinophilic Asthma: An Expert Consensus Framework to Characterize Phenotypes in a Global Real-Life Severe Asthma Cohort. Chest. 2021;160(3):814-830. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.013

15. NUCALA [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GSK; 2022.