Zika: Babies' Heads Looked Normal, then Stopped Growing

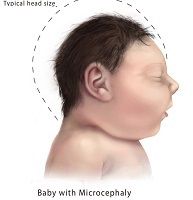

Babies exposed to Zika virus in utero can look normal at birth but develop microcephaly months later as their head growth decelerates, the CDC reports.

Even when babies exposed in utero to the Zika virus appear normal at birth, they can develop microcephaly later, Brazilian researchers report.

Severe brain abnormalities are also common in these infants, the team found.

Writing in the current issue of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review, Vanessa van der Linden, MD, of the Association for Assistance of Disabled Children in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil, and colleagues at other institutions in Brazil and at the CDC, report on 13 infants in Brazil. All had laboratory evidence of congenital Zika virus infection, but they had only slightly smaller than normal head size at birth.

But as 11 of these infants grew, their heads did not grow as they should. Within months of birth it became apparent that their heads were growing too slowly.

“All infants showed a decrease in the rate of head circumference growth between birth and the time of the last examination,” the authors wrote.

They met the definition of microcephaly because at five to 12-month follow-up after birth their head measurements were more than two standard deviations below the mean for age and sex.

The remaining two infants of 13 in the study were referred for neurologic evaluation at ages five and seven months because of developmental concerns.

All 13 babies had brain abnormalities that could be seen on neuroimaging and were consistent with congenital Zika syndrome.

Among their birth anomalies were hearing problems, a tendency to have seizures, hip dysplasia, and bilateral dislocated hips. Several had signs of cerebral palsy.

Craniofacial disproportion was noted in six infants; three had redundant skin on the scalp at birth.

The researchers said they did not know the mechanism of the postnatal microcephaly.

“The decrease in head growth might be the consequence of earlier in utero destruction of neuroprogenitor or other neural cells, persistent inflammatory response-associated molecules, or continued infection of neural cells,” they wrote.

They also found that three of the infants’ prenatal ultrasounds had not picked up any indications of Zika damage.