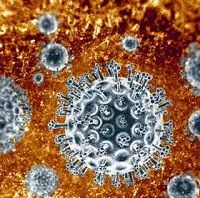

Are Pan-Genotypics a Panacea for HCV?

The list of effective drugs for the once incurable illness of hepatitis C infection keeps growing. But some physicians are frustrated. Here's why.

The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) shifted the treatment target of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection from management to cure.

Now the newest DAAs are demonstrating they are effective against multiple genotypes of HCV. This pan-genotypic activity promises simpler treatment regimens that could benefit a broader range of patients.

Are these drugs a panacea for HCV?

They may well be, but treatment barriers remain.

In a strongly expressed viewpoint on the cost of HCV therapies in the U.S., posted online in July in the Lancet Infectious Diseases, Brian Edlin, MD., Weill Cornell Medical College, and Institute for Infectious Disease Research, National Development and Research Institutes, in New York City points out that coverage of the new DAAs by many state Medicaid programs and at least two of the nation's largest private insurers is limited to only those patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis..

"The pricing and payer restrictions effectively mean that the U.S. Healthcare system has, for the first time, widely adopted a policy of rationing curative medical treatment for a life-threatening communicable disease," Edlin declared.

David Bernstein, MD, Chief of Hepatology, Sandra Atlas Bass Center for Liver Diseases and Professor of Medicine, Hofstra-Northwell School of Medicine, Hempstead, NY expressed similar concerns to MD Magazine, although noting that the best treatment for a particular patient is not necessarily the newest.

"There are other regimens that are equally efficacious by specific genotype but not pan-genotypic," he pointed out," and payer formulary is very important here."

Bernstein objects, however, to efficacious treatment for HCV being delayed because of payor policy.

"We should be giving the best regimen to whatever patients need it," he said. "It costs a lot of money to the healthcare systems to wait before one initiates therapy, as people will get sick from a multitude of things."

Meanwhile, the pan-genotypic HCV drug list is growing quickly.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the fixed-dose oral tablet combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir, (Epclusa/Gilead Sciences) June 28 as the first all oral pan-genotypic single tablet regimen to treat all six major forms of chronic HCV infection.

Approval in the US followed evidence from phase III clinical trials that 95 to 99 percent of patients--adults with genotypes 1 to 6 chronic HCV without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis--appeared to be cured with 12 weeks of treatment. The subjects had a sustained virological response (SVR) with no detectable virus in the blood 12 weeks after finishing treatment.

The approval also marked the first single tablet regimen to treat HCV genotype 2 and 3 without the addition of the older antiviral ribavirin (Copegus, Genentec; others). An additional trial in the FDA application demonstrated that 12 weeks of the sofosbuvir and velpatasvir combination oral tablet administered along with ribavirin produced a cure rate of 94 percent in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

In the FDA announcement, Edward Cox, MD, Director of the FDA Office of Antimicrobial Products, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said, "This approval offers a management and treatment option for a wider scope of patients with chronic hepatitis C."

The pan-genotypics achieve their broad spectrum and relatively high threshold against resistant viral mutations by acting on viral sites which are essential across genotypes for replication or stability.

Even with pan-genotypic activity, however, one DAA is not used as monotherapy, but in a regimen that targets and disrupts multiple sites on HCV to avoid resistant mutation and to achieve SVR.

A pan-genotypic can be used with ribavirin, and/or another DAA which has a complementary site of action but not necessarily pan-genotypic activity or as high a threshold against resistance.

The combination of the DAA grazoprevir with the pan-genotypic elbasivir (Zepatier/ Merck), for example, was approved by the FDA in January for HCV types 1 and 4. The pan-genotypic DAA, daclatasvir (Daklinza, Bristol-Myers Squibb) in combination with the single-entity formulation of the pan-genotypic sofosbuvir (Sovaldi/Gilead) was approved by the FDA in July of 2015 to treat the more difficult HCV type 3 genotype infection, without need for ribavirin, or interferon. The combined use of daclatasvir and sofosbuvir from the respective manufacturers was also approved earlier this year in Europe to treat types 1,2,3, 4 chronic hepatitis C including some types occurring with decompensated cirrhosis, HIV co-infection, and post-liver transplant recurrence of HCV.

Other pan-genotypics are in the development pipeline. The combined use of investigational agents from AbbVie (ABT-530) and Enanta Pharmaceuticals (ABT-493), for example, was reported at the International Liver Congress in April to have demonstrated efficacy in HCV genotype 3 infection with cirrhosis.

A pan-genotypic combined with another DAA and/or with ribavirin, has also enabled "interferon-free" treatment regimens. Although peginterferon (PegIFN) alpha-2a (Pegasys, Genentech) or alpha-2b (PegIntron/Merck) has been a staple of HCV treatment, it isn't tolerated by the most seriously ill patients with advanced or decompensated liver disease. PegIFN continues to have a role in the pan-genotypic DAA era, however, and its use in a triple regimen with a pan-genotypic DAA and ribavirin has been suggested as an option for HCV type 3 patients with less advanced cirrhosis who have not responded to DAA therapy.

A combination of one pan-genotypic with the older, non-DAA agents may also be more accessible for a range of patients, according to a recent review by Avik Majumdar, M.D., Department of Gastroenterololgy, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria., Australia, and colleagues.

"It is likely to be less expensive and by inference more cost-effective making it a potentially important regimen for health-resource poor countries," they wrote.

In the U.S., the list price, Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC), in 2015 for 12-week regimens for HCV treatment-naive genotype 1, without factoring group purchasing or manufacturers' patient assistance program discounts, ranged from $54,600 to $94,500 for commonly recommend therapies and up to $147,000 for the combined use of the two pan-genotypics, daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir. (Hepatitis C Online, University of Washington).

That price should not figure into treatment decisions, Bernstein said, particularly if that means delaying prescribing these new drugs when they are the patient's best option.

"Why would you wait for someone who has diabetes to develop kidney disease or eye disease?" he asked, "You want to treat as soon as you can before you develop problems--why would you wait for someone with hypertension to have a stroke before you start treating them?"

"I think the same is true here [with HCV]," Bernstein said. "If you have someone who has the disease, you should treat it and get rid of it."