Efficacy of Beta-Blockers in Patients with Heart Failure Plus Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) often coexist. The use of beta-blockers in HF patients has a class 1A recommendation in both the European and American guidelines. In current guidelines for heart failure therapy, the recommendation for beta-blockers is not restricted to patients with sinus rhythm, and includes all HF patients.

Karla K. Quevedo, MD

Review

Kotecha D, Holmes J, Krum H, et al. Efficacy of beta-blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61373-1378.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) often coexist. The use of beta-blockers in HF patients has a class 1A recommendation in both the European and American guidelines. In current guidelines for heart failure therapy, the recommendation for beta-blockers is not restricted to patients with sinus rhythm, and includes all HF patients. The objective of the study by Kotecha et al was to assess the efficacy of beta-blockers in patients with symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation.

Study Details

The study included 11 randomized clinical trials. Selected trials had more than 300 patients and planned follow-up for more than 6 months. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, including an analysis of total mortality where deaths occurred after early study termination or following a fixed censor point. The mean follow-up period until death or censoring was 1.5 years. Major secondary outcomes were cardiovascular (CV) death, the composite of all-cause mortality, CV hospitalization, and nonfatal stroke. A post hoc defined outcome was the composite of CVdeath and HF-related hospitalization. Drug safety outcomes were focused on discontinuation of study drug therapy due to hypotension, bradycardia, renal impairment, HF exacerbation, or any adverse event. Diagnosis of AF or atrial flutter was determined by the baseline electrocardiogram (ECG). Atrial flutter accounted for only 4% of the combined group. Incident AF was defined as AF during follow-up. Follow-up ECGs or adverse event data were missed in 6% of the patients. The primary and major secondary outcomes were analyzed using a stratified Cox proportional hazards regression model.

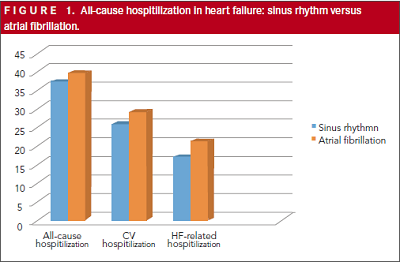

A total of 18,254 participants were assessed; 76.4% were in sinus rhythm and 16.8% in AF. Other rhythms (predominantly paced rhythm or heart block) were 6.2%. The median duration of HF was 3 years. Compared with those in sinus rhythm, AF patients were 5 years older, predominantly male, more symptomatic, and had more frequent use of diuretics, aldosterone antagonists, digoxin, and oral anticoagulants. Overall mortality was 20.7% in AF and 16.0% in sinus rhythm. When deaths were analyzed according to beta-blocker use versus placebo, beta-blockers were associated with a highly significant 27% reduction in all-cause death among patients in normal sinus rhythm. The most common causes of death in both groups were sudden death and death due to heart failure. Fatal stroke was uncommon and more frequent in AF. The total number of hospitalizations and annualized rate of hospitalizations per patient were higher in AF patients, with longer average length of stay (Figure 1).

A consistent efficacy of beta-blockers was noted across all death and/or hospitalization outcomes in the sinus rhythm group, but no significant differences were seen in AF patients. Beta-blockers had no impact on incident nonfatal stroke in sinus rhythm or AF. An exploratory subgroup analysis was performed within the AF cohort for all-cause mortality, with no significant interactions identified for a range of variables, including age, gender, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), NYHA class, control of blood pressure or heart rate, and baseline medical therapy. Allocation to beta-blockers was associated with a 33% reduction in the adjusted odds of incident AF. Rates of study drug discontinuation due to adverse effects were identical in patients allocated to either beta-blockers or placebo. Patients with AF had higher crude rates of death, more frequent hospitalization, and longer length of stay compared with those in sinus rhythm.

The strength of the study was the use of an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis from large, high-quality randomized controlled trials. The limitations of the study are missing data for some variables. There was not a distinction between AF and atrial flutter, so a conclusion cannot be applied for both groups. The incidence of AF was lower than expected and could represent underreporting, with missing cases of paroxysmal AF. There was not characterization of the type, persistence, and duration of AF.

The main findings of the study were that in contrast to those in sinus rhythm at baseline, patients with HF and AF obtained minimal or no benefit from beta-blockers, with no significant reduction in all-cause mortality, CV hospitalization, or composite clinical outcomes compared with placebo. Of note,it did appear safe to use beta-blockers in patients with HF and AF, with no increase in mortality or hospitalization.

Commentary

AF and HF have a negative impact on each other

The lifetime risk of developing HF is 20% for Americans older than 40 years.1 Although survival has improved, the absolute mortality rates for HF remain approximately 50% within 5 years of diagnosis.2 HF is the primary diagnosis in more than 1 million hospitalizations annually. The total cost of HF care in the United States exceeds $30 billion annually, with over half of that spent on hospitalizations.3 HF significantly decreases health-related quality of life, especially in the areas of physical functioning and vitality.4

Patients with HF are more likely than the general population to develop AF.There is a direct relationship between the NYHA class and the prevalence of AF in patients with HF. AF is also a strong independent risk factor for subsequent development of HF. HF and AF can interact to promote the perpetuation and worsening of both conditions through mechanisms such as rate-dependent worsening of cardiac function, fibrosis, and activation of neuro-humoral vasoconstrictors. AF can worsen symptoms in patients with HF, and conversely, worsened HF can promote a rapid ventricular response in AF.5

General principles of HF management include correction of underlying causes of AF and HF, as well as optimization of HF management. The use of 1 of the 3 beta-blockers proved to reduce mortality (bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol succinate) is recommended for all patients with current or prior symptoms of HF with reduced ejection fraction, unless contraindicated, to reduce morbidity and mortality (Class I, Level of Evidence A).6

As recommended by the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society Guideline for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, the use of beta-blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists for control of ventricular rate inpatients with paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent AF is a Class IB recommendation.7 There is a specific recommendation for patients who have both HF and AF. The use of beta-blockers in patients with AF and HF with preserved ejection fraction is a Class IB recommendation.7 One study had focused on the specific group of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction and AF.

Studies have focused on the specific group of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction and AF. Important clinical considerations in this population are age, comorbidities, prior history of coronary artery disease, beta-blocker titration, and target heart rate. The study by Ivan Stankovic8 on sinus rhythm versus atrial fibrillation in elderly patients with chronic heart failure provided some insights about titration of beta-blockers. The mean age of this population was 72 years; mean ejection fraction was 37%. The study was designed to compare sinus rhythm versus AF in elderly patients. Patients with AF had lower ejection fraction, exercise capacity, self-rated health, and quality of life, and higher NYHA class. Beta-blocker titration was associated with clinical improvement, improvement of ejection fraction, 6-minute walk distance, and NYHA class.8 Thereare no data about supervised titration of beta-blockers in the study by Kotecha et al.

In patients with AF, with or without HF, lower heart rate has not been associated with better outcomes.10 Heart rate control (resting heart rate <80 beats per minute [bpm]) strategy is reasonable for symptomatic management of AF (Class, Level of EvidenceB).7 The mean heart rate in the AF group was 81 bpm (range, 72-92 bpm). It would be interesting to perform a multivariable analysis to evaluate if AF patients with more aggressive rate control had worse outcomes.

Another observation derived from the study by Kotecha et al is that the AF group was older (mean of 64 years in the sinus rhythm group versus a mean of 69 years in the AF group), had worse symptoms, and were using more amiodarone and digoxin compared with the sinus rhythm group. Older age and NYHA class are recognized risk factors for HF and increased hospital admission, which could contribute to the findings in the AF group. Side effects related to chronic use of amiodarone and digoxin can also be considered as variables that could contribute to increased hospital admission observed in the AF group.

The incidence of AF could be underestimated in Kotecha’s study. Incidental cases of AF were observed and documented; however, follow-up ECGs were missed in 6% of the patients.

As discussed earlier, AF and HF have a negative impact on one another and adversely affect mortality when found together. The poor prognosis of concomitant AFand HF is a consistent finding in several HF trials,leading to increased hospitalization and lengthier inpatient stays. AF with rapid ventricular response (RVR) can precipitate an episode of heart failure with a requirement for hospitalization. Rate control is indicated for treatment of patients with AF and RVR. Beta-blockers have proved to be an effective measure for rate control in these patients. It seems contradictory that the use of beta-blockers did not reduce all-cause mortality, CV hospitalization, or composite clinical outcomes compared with placebo. Because of several limitations and confounding variables, the results of the study cannot immediately be applied to clinical practice.

It is important to emphasize the higher morbidity, mortality, and economic burden associated with HF patients with reduced ejection fraction and AF. The past decade has seen substantial progress in the understanding of the mechanisms of AF, implementation of ablation, and new drugs for stroke prevention. However, further studies are needed to better inform clinicians about the risks and benefits of therapeutic and preventive options for individual heart failure patients.

References

1. Djousse L, Driver JA, Gaziano JM. Relation between modifiable lifestyle factors and lifetime risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2009;302:394-400.

2. Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004; 292:344-350.

3. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6-e245.

4. Lesman-Leegte I, Jaarsma T, Coyne JC, et al. Quality of life and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a comparison between patients with heart failure and age- and gender-matched community controls. J Card Fail. 2009;15:17-23.

5. Maisel WH, Stevenson LW. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:2D-8D.

6. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327.

7. January CT, Wann S, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelinesand the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:e199-e267.

8. Stankovic I, Neskovic AN, Putnikovic B, et al. Sinus rhythm versus atrial fibrillation in elderly patients with chronic heart failure — insight from the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study in Elderly. IntJCardiol.2012;161:160-165

9. Khazanie P. Outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. JACC: Heart Fail.2014;2:41-48.

10. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijing HF, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363-1373.

About the Author

Karla K. Quevedo, MD, is a cardiology fellow at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in El Paso. Dr Quevedo received her MD degree at the Universidad San Martin de Porres in Peru. She was chief resident in internal medicine at Guillermo Almenara Hospital in Lima, Peru. She is chief fellow in cardiovascular fellowship at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, El Paso. Her areas of interest are general cardiology, preventive cardiology, and heart failure and biomarkers.