Insufficient Efficacy of Fatigue Interventions for Pediatric Rheumatic Conditions

Although it is assumed that fatigue is related to inflammation, disease activity, or treatment with drugs such as Methotrexate, it can affect children independent of disease activity and impacted by psychosocial factors.

Factors such as a limited number of studies, risk bias, inconclusive outcomes, and non-comparable interventions contributed to the insufficient evidence of current interventions to reduce symptoms of fatigue in patients with Pediatric Rheumatic Conditions (PRCs), according to a study published in Pediatric Rheumatology.1 Investigators believe future studies should focus on underlying biological and psychosocial mechanisms of treatment to reduce fatigue in this patient population.

“Fatigue is a prevalent distressing symptom in children and adolescents with Pediatric Rheumatic Conditions (PRCs) and can have a significant impact on the well-being and participation in the daily life of the patient and his or her family,” investigators explained. “The ability to early and adequately assess, treat and reduce the severity of fatigue can improve their current well-being and participation in daily life, as well as their future well-being by preventing fatigue from becoming persistent.”

Although it is assumed that fatigue is related to inflammation, disease activity, or treatment with drugs such as Methotrexate, it can affect children independent of disease activity and impacted by psychosocial factors.

Investigators searched articles published on PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science and Cinahl. Bias was assessed and the systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Randomized or controlled intervention trials that analyzed patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), Childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE), or juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) were included. All articles dealt with fatigue as a primary or secondary outcome. Those that were not available in full text versions were excluded. Attempts to contact lead investigators were made in cases of missing data and a quality assessment of the information was added.

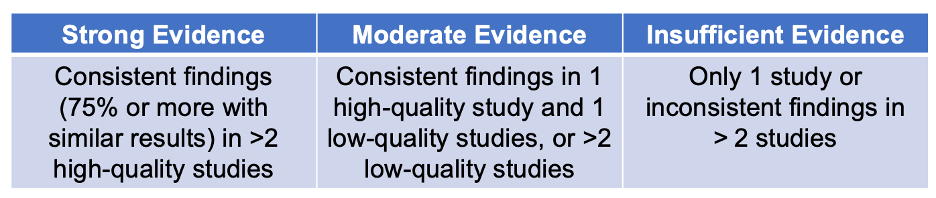

Quality scores were based on the following levels of evidence:

Of 418 studies, 10 were included for analysis, with a total of 240 participants (aged 5 to 23 years). Common themes for interventions were exercise therapy, receiving prednisolone, vitamin-D supplements, psychological therapy, and transitioning into an adult rheumatology program. Efficacy of these measures was determined via self-reported questionnaires.

Four studies evaluated exercises therapy (3 using land-based therapy and 1 studying aquatic-based therapy). Three analyzed medication and nutritional supplements, 2 studied psychological or cognitive behavioral interventions, and 1 determined the efficacy of a transitioning children into an adult program. All 10 studies were further categorized into 3 groups: exercise therapy, medication/supplements, or psychological/transition program.

Six of the 10 studies had a high risk of bias, 3 had moderate risk, and only 1 had a low risk.

The efficacy of fatigue interventions was contradictory among most studies. For example, land-based exercise was an effective strategy in 1 study, but not effective in another 2 trials. However, aquatic-based therapy was more effective than land-based. Although cognitive therapy showed promise in 1 study, another did not show any difference in reducing symptoms of fatigue.

While creatine was not an effective strategy, a 7-day dose of prednisolone or 6 months of vitamin-D supplementation appeared to reduce fatigue in these patients. Both studies were determined to have a high risk of bias and not comparable.

The transition program showed a small positive effect but was not enough to be clinically significant.

Psychological intervention demonstrated an insignificant difference in reducing fatigue between the cohort that received 6 sessions and the group that attended 12. However, investigators stated that patients with JIA do benefit from psychological intervention techniques.

Although the study was strengthened by its focus on fatigue interventions, it was limited by the small number of studies analyzed and the inconclusive findings. Intervention procedures, study designs, and outcome-measuring tools further added to the difficulty of determining efficacy.

“There is an urgent need for more intervention studies that primary aim at the treatment of fatigue in children and adolescents with PRCs,” investigators concluded. “Future studies should investigate interventions applying a multifactorial approach of fatigue, and therefore be aimed at the physical and psychosocial dimensions to fatigue, combined with an assessment to determine fatigue in relation to physical, environmental, and personal outcome parameters.”

Reference:

Kant-Smits K, Van Brussel M, Nijhof S, Van der Net J. Reducing fatigue in pediatric rheumatic conditions: a systematic review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19(1):111. Published 2021 Jul 8. doi:10.1186/s12969-021-00580-8