Medicine and Miracles

An Ontario historian and hematologist has become perhaps the world's leading expert on the role medicine has historically played in how miracles are assessed by the Catholic Church as part of its process to grant sainthood.

Jacalyn Mary Duffin, MD, PhD, is no saint.

In fact, the Ontario medical school professor/hematologist/historian will cheerfully tell you, she's an atheist.

But the subject of saintliness has permeated many of her scholarly thoughts for almost 3 decades, says Duffin (known to friends as Jackie). Through the intervention of providence, divine or otherwise—but set in motion by a very personal tragedy—Duffin has become perhaps the world’s leading expert on the role medicine has historically played in how miracles are assessed by the Catholic Church as part of its process to grant, or deny, sainthood.

"Ninety-nine percent of miracles [used in support of eventual sainthood] are medically based,” Duffin says. Thanks to her unprecedented and intensive research in the Vatican archives, beginning with a sabbatical visit there in 2001, she was the first historian to be able to state that with certainty.

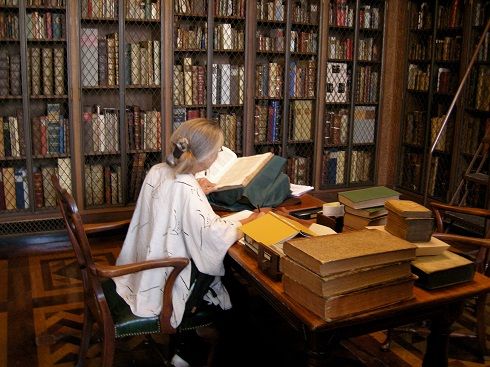

Later in the 2000s, she spent somewhere between 10 and 15 academic breaks, all lasting a week or more, in the archives.

“You can’t get to be a saint without working a miracle after your death,” explains Duffin, who was raised Protestant. She personally read, in the original Vatican files, at least one miracle believed to have been performed by virtually every person who achieved sainthood between 1588 and 1999. In total, she says, “I examined more than 1,400 miracles from more than 400 canonizations of more than 400 saints.”

The result was her groundbreaking 2009 book, “Medical Miracles: Doctors, Saints, and Healing,” (Oxford).

This month, 64-year-old Duffin, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada who holds the Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, will be the keynote speaker at the Canadian Catholic Historical Association. Her talk will draw from her most recent monograph, "Medical Saints: Cosmas and Damian in a Postmodern World" (Oxford, 2013).

Practicing in what is now Syria, Cosmas and Damian were physicians who charged patients no fees. “They were supposedly twin brothers, martyred around 303 AD when they were executed by the Roman emperor Diocletian, who killed a lot of Christians,” explains Duffin. Later, they became viewed as patron saints of medicine, surgery, and pharmacy by the Byzantines, the Medicis of Florence, and countless other faithful to this day.

A love of history extends back to Duffin’s childhood. "I grew up with a map of ancient Egypt on my bedroom wall,” Duffin recalls of her youth in London, Ontario.

“When I was a kid, and all the way through high school, I thought I would end up studying history, especially archeology. But in grade 13, I had the idea that I could help people, so I switched all of my subjects to science, applied to a combined college/medical-school program, got accepted, and got a scholarship,” she says, adding that the financial aid was crucial since her father had died about 6 years earlier. “People said, ‘Oh, you can always do history as a hobby.’”

Duffin earned her MD from the University of Toronto in 1974. She married a fellow physician, Hugh Lansing (Lance) Lipton, relocated to Thunder Bay, Ontario, and gave birth to son Joshua in 1977. In 1979, she finished a fellowship in internal medicine and hematology.

Then, in a moment, everything changed: Lipton was killed in a bicycle accident when Joshua was just 4, in 1981.

The blow was immeasurable, but in its aftermath Duffin grew closer to “a very old friend,” Robert Wolfe, PhD, a Canadian diplomat posted to Paris. “We wrote lots of letters and decided over the phone to get married,” Duffin remembers. They wed in 1982, and Duffin and Joshua moved to France.

One problem: “I couldn’t get a job,” Duffin says wryly. “The French didn’t recognize my Canadian medical degree, I couldn’t work on a spouse’s diplomatic visa, and all the doors seemed to be closing.

“It was a really difficult time. My husband was working, my son was in school, and how many museums can you go to?” she asks rhetorically. “I had to find something to do with my time, so I thought about studying the history of medicine.” That brainstorm eventually resulted in a PhD awarded in 1985 by the Sorbonne, for her thesis on the history of the stethoscope.

After the family returned to Canada later in 1985—expanded by one, with the birth of daughter Jessica in 1983—Duffin again encountered employment woes. But opportunity knocked with the chance to do locums for hematologists at Ottawa General Hospital and to prove that she could read slides as well as ever.

“At the end of 3 years they realized I wasn’t dangerous,” Duffin says with a touch of humor, “and I was offered a job there in Ottawa—at the same time as I was offered the history job at Queen's University in Kingston. The latter is the one I’ve now been lucky enough to have for 27 years, a historian in the medical school and practicing hematologist as well.”

The intersection of Duffin’s career with the Catholic Church began in 1986 or 1987, during her “freelancing” period, when her colleague, Jeanne Drouin, MD, presented her with a set of slides and a request for Duffin to report her conclusions.

“The patient’s diagnosis was acute myeloblastic leukemia, for which the median survival is about a year and a half,” remembers Duffin. “The first thing that came to mind was that there must be some problem, possibly a lawsuit. One reason was that the slides were dated about 8 years earlier. I assumed the patient was dead.

“There were 20 trays of slides, of blood and bone marrow samples done each month over 18 months. I wrote a report as if I were the laboratory pathologist—those bone marrows told a story. There was terrible leukemia, then remission—normal for about 4 months—then a relapse, more treatment and remission again.

“I was given no clinical information. At the end of the slides, the second remission comes along, and you can see it’s normal…normal…normal…then the slides stopped, and I thought maybe she died of an infection. Because she had lived the average life expectancy, even longer, and of course remissions do tend to get shorter and shorter,” Duffin notes.

“I handed the report to my friend Jeanne, and she told me the patient hadn’t died—she was still living, 8 years later!” What’s more, at that point, Drouin said, treatment consisted only of monitoring her condition, which was stable—3 years earlier, the patient had requested that maintenance chemotherapy be stopped.

“There was no way that person could have lived without continuing chemotherapy,” Duffin remembers thinking—and that was exactly the point. The patient believed her survival was a literal miracle, one facilitated by the long-deceased French-Canadian nun Marie-Marguerite d’Youville (1701-1771).

At the time of the patient’s ordeal, d’Youville was the subject of a canonization proceeding within the Catholic Church. She had already been beatified, the first major step in the canonization process. In order to become a saint, however, the Vatican needed to verify that d’Youville had worked a miracle after her death. In order to do that, the church recruited a “perfectly ignorant” (ie, unbiased) witness who could expertly attest that there was no scientific explanation for the patient’s continued survival. Unbeknownst to her, Duffin was that expert.

Consequently, Marie-Marguerite d’Youville, founder in 1737—as a widow—of a charitable/medical order later known informally as the “Grey Nuns,” was canonized in 1990, the first native-born Canadian to be elevated to sainthood.

Duffin was invited to attend the Vatican sainthood ceremony, and Father Constantin Bouchaud, who served as a Canadian church representative in Rome, presented her with a copy of “the book of the miracle,” says Duffin. “‘I thought you’d like to have this,’ he said, and inside was all the testimony, mine, everyone’s. ‘Wow, I’m going to be in the Vatican archives,’ I thought.”

Historian that she is, Duffin’s next thought was that every canonization-related miracle must have such a book in the Vatican archives—and wouldn’t it be interesting to peruse them? So, in addition to her other academic and family responsibilities, she made the time to plan what would grow to become Medical Miracles.

“Never in a million years did I initially think I would be able to do this, but I thought it might be fun to see if it were possible…would the archives let me in? Would they let me read the files? But within the first hour [in 2001],” Duffin exults, “I was being given access to these marvelous records.” Soon enough, the Vatican scholars who staff the archives knew her as “the miracle lady.”

She methodically combed through the testimonies for about 400 canonizations from 1588—when the current rules were enacted—through 1999.

“The vast majority were handwritten in the native tongue of the person who had been healed,” says Duffin, and her knowledge of Latin and various Romance languages got her through the first 200 years easily enough. When she hit the late 18th century, testimonies began appearing in German, “which I can stumble through,” and Polish and Flemish and Catalan, which she could not—but she relied in those instances on the Latin, and later Italian, translations.

“I stayed away from the sections on theology and religion, and focused on the medical: If there was a disease, what was it? Was there a doctor involved? What did he say? I got really good at mining those files,” Duffin says with a smile. “And I loved doing the work—the quirkiness of the documents, reading them in these wonderful spaces filled with art by the greatest artists in the world. Besides that, I love Rome. I think I was a Roman in a previous life.”

Given her love of history, it’s not surprising that Duffin passionately advocates for the study of medical history to be integral to medical education. Her book “History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction” (University of Toronto, 1999, 2nd ed. 2010) is widely assigned in college and graduate courses. Last year, she co-authored the Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences article “Making the Case for History in Medical Education.”

Duffin has also published more than 50 journal articles and 3 books beyond those mentioned above, edited 2 anthologies, co-translated (from French) a history of AIDS, and is currently researching topics ranging from early 19th-century Roman hospitals to a Canadian medical expedition to Easter Island in the 1960s.

Of her “works,” she is by far proudest of Joshua and Jessica, now 38 and 31. Joshua lives in regrettably distant Brisbane, Australia, with his wife—both are physicists—and their 2 sons. Toronto-based Jessica “has a PhD in English literature and book history,” Duffin beams, “and we actually collaborated recently on a CMAJ [Canadian Medical Association Journal] review of a Toronto exhibit on the anatomist Andreas Vesalius. It was a thrill to work together on a topic that was of great interest to us both and to find that my daughter brought her own special expertise to the project in ways that I could not have imagined.”

Duffin’s pride extends to her brother, Ross W. Duffin, DMA, the Fynette H. Kulas Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve University and director of the undergraduate and graduate programs in early music. “His book, ‘Shakespeare’s Songbook’ [Norton, 2004], is brilliant,” Duffin attests admiringly.

“Our father died when Ross was 11 and I was 12. Our mother had been a war bride. After her husband died, she went out and got a job, first as a university secretary,” Duffin recalls. “Then she did a degree in classics and became a high school teacher. She had such respect for scholarship.

“We credit her,” Duffin says emphatically, “with our careers.”

In Duffin’s case, it’s a career that, one might say, has turned out heavenly in more ways than one.

Photo Credits:

Top: Robert David Wolfe, taken at the New York Academy of Medicine

Middle: B. Clark for Queen's University