Researchers Identify Possible Source of Pancreatic Complications Associated with Cystic Fibrosis

A new investigation of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that produce diabetes may explain the strong association between cystic fibrosis and pancreatic complications.

A new investigation of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that produce diabetes may explain the strong association between cystic fibrosis and pancreatic complications.

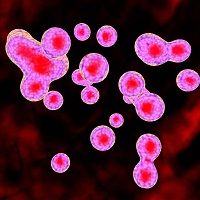

Researchers from Johns Hopkins University and a genomics research institute in Barcelona hypothesized that adult centroacinar cells are progenitors to the beta (β) cells that reside in the pancreas and produce insulin in humans and other animals.

The study team chose to use larval zebra fish to test its hypothesis because the pancreatic cells of such creatures regenerate readily and it chose to test the hypothesis with 2 complementary approaches. First, it used lineage tracing to demonstrate that centroacinar cells form new endocrine cells following β-cell ablation or partial pancreatectomy. Second, it sought to establish the transcriptome for adult centroacinar cells.

In doing this second test, team member used gene ontology, transgenic lines and in situ hybridization to find that the centroacinar cell transcriptome is enriched for progenitor markers.

“We concluded that CACs and their larval predecessors are the same cell type and represent an opportune model by which to study both β-cell neogenesis and β-cell regeneration,” the study authors wrote in Diabetes. “Furthermore, we show that in cftr loss-of-function mutants there is a deficiency of larval CACs, providing a possible explanation for pancreatic complications associated with cystic fibrosis.”

The literature linking β cells and diabetes is, of course, enormous. β cells produce, store and release the hormone insulin. Type 1 diabetes is a result of a misguided attack by the body’s immune system on its own β cells.

It remains unclear why, exactly, the immune system does this. Research in mice indicates that the process begins when disease stresses β cells and that stress somehow triggers immune attack.

β cell failure also plays a role in type 2 diabetes, which occurs when the body becomes resistant to insulin. βcells compensate by producing more insulin and, eventually, they seem to wear out.

The literature linking β cells and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, on the other hand, is scarce. Indeed, it is largely limited to a number of studies that note diabetics are unusually prone to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. According to a recent research review that appeared in the International Journal of Endocrinology, papers that have looked for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in people with type 1 diabetes have found it in 25% to 74% of all subjects, while papers that have looked for it in people with type 2 diabetes have found it in 28% to 54% of all subjects.

The association between diabetes and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency was first spotted in the 1960s, but only in more recent years, with the invention of non-invasive tests for endocrine pancreatic insufficiency and the explosion of diabetes research, has it become well documented.

“As the prevalence of diabetes in the general population is much higher than that of chronic pancreatitis, this relationship is potentially of great clinical relevance,” the review authors wrote earlier this year. “A long disease duration, high insulin requirement, and poor glycemic control seem to be risk factors for PEI occurrence. The impact of pancreatic exocrine replacement therapy on glycemic, insulin, and incretins profiles has not been fully elucidated.”

As for the connection between cystic fibrosis and β cells, the link again goes through diabetes, or, at least, a special subtype of the condition known as cystic fibrosis-related diabetes that comes about from causes that have yet to be fully identified.