Article

Spotting the early warning signs of aggressive RA

Recent advances in drug therapies for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have increased the importance of early intervention. Several serological testing and imaging techniques help facilitate early diagnosis. C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate have limitations in predicting RA. Rheumatoid factor acts as a prognostic marker for later joint damage in patients with early RA. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide can predict more erosive disease. Radiography currently is the marker for structural damage in RA, but it cannot detect soft tissue changes or actual cartilage deterioration. MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality. Ultrasonography has been shown to be more sensitive than conventional radiography in detecting erosions. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:110-115)

ABSTRACT: Recent advances in drug therapies for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have increased the importance of early intervention. Several serological testing and imaging techniques help facilitate early diagnosis. C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate have limitations in predicting RA. Rheumatoid factor acts as a prognostic marker for later joint damage in patients with early RA. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide can predict more erosive disease. Radiography currently is the marker for structural damage in RA, but it cannot detect soft tissue changes or actual cartilage deterioration. MRI is the most sensitive imaging modality. Ultrasonography has been shown to be more sensitive than conventional radiography in detecting erosions. (J Musculoskel Med. 2008;25:110-115)

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) often presents late, when irreversible damage has occurred. More than half of primary care consultations are for joint pain,1 but the average time from initial presentation with symptoms to confirmation of diagnosis of RA is 18 weeks.2

Recent advances in drug therapies for RA have increased the importance of early intervention. Therefore, early diagnosis has never been more critical. Many diagnostic tests are available; physicians should select them carefully in an effort to improve the time to diagnosis.

Serological testing and imaging techniques are becoming increasingly useful in facilitating early diagnosis of RA and appropriate disease monitoring in primary care practice. Because there are so many tests, however, gaining an understanding of the value and application of each technique is difficult. In this article, we provide an overview of serological testing and imaging techniques and how they are applied in the diagnosis and management of early RA.

WHY EARLY DETECTION IS NEEDED

A major goal in the treatment of patients with RA is the prevention of erosive joint disease and the irreversible functional disability that might result from it.3 Combinations of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and, more recently, biologic agents (eg, those blocking tumor necrosis factor α) are used in clinical practice to achieve this goal. Key to the prevention of joint damage is the ability to identify inflammatory disease at the earliest time, when disease activity is reversible. Such early recognition of inflammatory disease and subsequent aggressive treatment allow for prevention or modulation of erosive disease to a less severe phenotype.

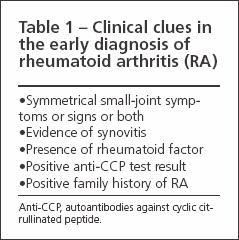

Physicians should have a high index of suspicion when patients present with key clinical symptoms (Table 1). Appropriate diagnostic tests should be ordered, but first it is important to consider the aims of any rheumatologic investigation: to assist with diagnosis, to provide guidance for prognosis, and to assess disease activity. Serological markers, including those that indicate diagnosis and prognosis, as well as radiographic, ultrasonographic, and computerized imaging techniques, are used to determine outcome measures in clinical trials.

SEROLOGICAL MARKERS

Acute phase reactants

C-reactive protein (CRP) and other acute phase reactants are proteins that the liver produces in higher quantities as part of the acute phase response to an inflammatory stimulus. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is also used frequently as a measure of the acute phase response. ESR provides an indirect measure of the amount of fibrinogen in the blood; production of fibrinogen is increased as part of the acute phase. An elevated acute phase response has been shown to correlate with bone damage,4 loss of bone mineral density (BMD),5 and functional impairment, especially when it is analyzed as the “area under the curve” (that is, when it is expressed as cumulative exposure of the patient to an elevated CRP level, reflecting continuing inflammation).

When CRP is analyzed on a population basis, however, it does not predict RA.6 The CRP level may be normal at presentation in up to 60% of new patients with RA.7 Green and associates8 and van der Heijde suggested that baseline CRP may not be a predictor of persistence or disease severity in very early disease. In patients who have less than 12 weeks of symptoms, it has been suggested that outcome measures other than CRP should be used. Although in established disease the CRP level reflects the cytokine and overall inflammatory load (and, therefore, is a useful surrogate marker), in early disease it may not be helpful diagnostically in distinguishing among various forms of arthritis. Similarly, the ESR may not be helpful in diagnosis because an elevated level may be caused by physiological factors other than inflammation, such as anemia and elevated lipid levels.

Antibodies

The autoantibodies that are produced against the Fc portion of the IgG molecule are referred to as rheumatoid factors (RFs). IgM and IgA types of RF have been examined, and the role of RF in diagnosis and disease prognosis has been confirmed. In a cohort of patients with early RA, for example, van Zeben and colleagues9 showed that RF acts as a prognostic marker for later joint damage in early RA regardless of the test used to measure RF. Gough and coworkers10 demonstrated that a positive RF had a strong correlation with the development of erosions in a cohort of patients with early arthritis, independent of shared epitope; this finding emphasizes the predictive role that RF can play in patients who have early disease.

Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) are RA-specific IgG antibodies. In many patients, they have been shown to precede the onset of symptoms.11 Berglin and colleagues12 investigated 96 patients with early RA, who had donated blood when they were asymptomatic, and analyzed various biomarkers, including anti-CCP antibodies. Patients who had predating anti-CCP antibodies had significantly higher radiographic damage scores at disease onset and after 24 months of disease than those who did not; this finding confirmed that anti-CCP antibodies can predict more erosive disease.

van Gaalen and colleagues13 evaluated a prospective patient cohort to assess the predictive value of anti-CCP antibodies in patients with undifferentiated arthritis. They found that RA developed in 25% of patients who had a negative anti-CCP test result and in 93% of those who had a positive anti-CCP test result. Therefore, this autoantibody probably has most predictive value in the early phase of arthritis, when the diagnosis is unclear, and is especially useful in patients who are RF-negative.

Genetic markers also may play a role in diagnosis. Many studies have looked at the association between major histocompatibility genes, such as the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles, and the predisposition to RA. In particular, the “shared epitope” conserved amino acids of the HLA-DR4/DR1 cluster, which constitutes one of the peptide binding sites of some HLA-DR molecules associated with RA, have been shown to be a significant risk factor for RA.

Gough and associates10 showed that when compound heterozygotes or homozygotes for the shared epitope were studied, there was a significant relationship with persistence (relative risk [RR], 3.25; sensitivity, 23%; specificity, 91%) in early disease. They also showed that possession of the shared epitope or RF resulted in an RR of 13.49 for erosions (sensitivity, 95%; specificity, 39%).

Huang and coworkers14 showed that possession of the shared epitope correlates with synovitis score, as measured by the rate of gadolinium enhancement with MRI. However, such genetic testing is not routinely available in clinical practice and currently remains a research tool.

Some combinations of serological markers also have been studied in an effort to produce an improved diagnostic and prognostic effect. For example, Emery7 created a persistent inflammatory symmetrical arthritis (PISA) prognostic severity score for patients with arthritis of more than 12 weeks’ duration. Using 5 known prognostic factors for poor functional outcome and radiographic damage (RF, HLA-DR4 shared epitope, Health Assessment Questionnaire score, CRP, and female sex), he showed that patients with a total PISA score of 3 or higher have a poor outcome.

In addition, Raza and colleagues15 investigated the combination of RF and anti-CCP in patients with synovitis of 3 months’ duration. They showed that the combination had a high specificity and positive predictive value for the development of persistent RA.

IMAGING MODALITIES

Plain-film radiography

Because radiography is both relatively inexpensive and widely available, it is currently the marker for structural damage in RA. Hand and foot x-ray films are chosen because these anatomical areas are amenable to quantification and joint destruction is known to occur in them early in the disease course. The images now may be digitally recorded and retrieved; this allows for electronic transmission and standardized reading with reproducible scoring systems in the research setting.

Radiographs can detect many pathologic changes, such as erosions, joint-space narrowing, periarticular osteoporosis, and subluxation. However, in the earliest stages of RA, when the patient is pre-erosive, they are not helpful. In addition, they cannot detect soft tissue changes, such as the presence of synovitis. As a result, increasing interest has been directed toward use of MRI and musculoskeletal ultrasonography, which can identify such pathology at an earlier stage.

MRI

This is the most sensitive imaging modality, and its tomographic quality-including 3 orthogonal planes-helps provide a much greater field of view. MRI produces a highly detailed view of both the bony aspect of the joint and the surrounding soft tissues without exposing the patient to ionizing radiation-a considerable advantage over plain-film radiography, although disadvantages of MRI include high cost and lack of availability.

MRI is now available in several field strengths: the conventional high-field 1.5 Tesla magnet, the higher field 2 Tesla, and the new low-field 0.2 Tesla dedicated extremity. Sequences used in routine high-field MRI of musculoskeletal structures include T1-weighted images, which provide good anatomical detail; T2-weighted images, in which fluid/edema and fat produce a high signal; T2-weighted fat-suppressed images, in which bone edema is highlighted; short tau inversion recovery images; and T1 images obtained after intravenous injection of the contrast agent gadolinium. The gadolinium is preferentially taken up at sites of inflammation, such as synovitis; this allows for delineation from fluid collection and results in greater sensitivity in erosion detection.

Ostergaard and associates16 showed that MRI can identify most new bone erosions at least 1 year earlier than can conventional radiography. They found a significantly increased risk of progression of radiographic erosions in bones with baseline MRI erosions; this shows that MRI has value in prognosis of long-term radiographic outcome. In addition, MRI can identify pre-erosive features, such as synovitis and bone edema,17 and it allows for the identification of progressive erosive disease when clinical activity is suppressed.18

The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials MRI collaborative subgroup was set up to address interobserver variability and other issues. The subgroup has produced acceptable definitions and a valid scoring system for MRI findings in RA.19,20 The issue of validation in MRI has been addressed extensively with use of arthroscopy and synovial biopsy and comparison of them with MRI synovial volume estimates. This has been performed mainly in knees, as well as by mini-arthroscopy, macroscopic evaluation, and histology in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. Ostendorf and coworkers21 found that synovial enhancement postgadolinium on MRI correlated with macroscopic signs of synovitis and that joint-space narrowing on MRI was significantly correlated with bony changes on arthroscopy.

More work needs to be done before it can be concluded that MRI shows an accurate representation of erosive change, synovitis, and bone edema-the changes of inflammatory arthritis. MRI is more validated than ultrasonography as a technique, but currently available data suggest that findings on ultrasonography are equal to those on MRI when peripheral joints are assessed in patients with RA.22 Currently, therefore, MRI remains a research tool with no specific guidelines for use in individual patients, and its exact role in clinical practice remains to be defined.

Dedicated extremity MRI with use of a significantly smaller 0.2 Tesla magnet has many obvious advantages over its high-field counterpart. The cost is reduced significantly, and the machine may be positioned conveniently in a suitable clinic room rather than in the purpose-built home that conventional MRI requires. The machine consists of a “cradle” in which the peripheral joints of interest, such as the MCP joints of the dominant hand, are placed. This avoids difficulties of conventional MRI use, such as claustrophobia and the positioning of arthritic limbs. Disadvantages include smaller fields of view with longer imaging times and, because magnet strength is reduced, some reduction in image quality.

Some studies have investigated whether such reduction affects the ability to detect synovitis and erosions significantly. Taouli and coworkers23 compared conventional high-field–strength 1.5 Tesla MRI with 0.2 Tesla low-field dedicated extremity MRI and radiography in their ability to detect and grade bone erosions, joint-space narrowing, and synovitis in the hands and wrists of patients with RA (Figure 1). The results from use of the 2 field strengths were similar, although motion artefact limited the value of a few low-field studies. Lindegaard and colleagues24 compared low-field MRI with clinical examination. The results of low field MRI were significantly better; it could identify synovial hypertrophy in joints in patients who did not have clinical signs of joint inflammation (eg, swelling and tenderness).

Figure 1 – This low-field T1-weighted MRI scan shows widespread erosions in the wrist of a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

Ultrasonography

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography is extremely versatile; it allows the examiner to image many joints at the same sitting in a safe environment without x-ray exposure. The machines may be positioned in rheumatology outpatient clinics, which allows for immediate access as clinically indicated. In addition, ultrasonography is less expensive than CT and MRI.

Ultrasonography was shown to be more sensitive than conventional radiography in the detection of erosions.25 In the same study, sonographic erosions that were not visible on radiography corresponded by site to MRI bone abnormalities.

Hau and coworkers26 showed that ultrasonography provides better results than clinical examination alone. Wakefield and associates25 demonstrated its superiority to plain radiography. However, disadvantages of ultrasonography include lack of standardization and reliability; the modality’s interobserver and intraobserver variability are of particular concern.

Kraan and colleagues27 showed that ultrasonography and MRI both can detect subclinical synovitis with corroborative macroscopic and microscopic data from arthroscopy in clinically normal knees of patients with RA. Karim and coworkers28 compared ultrasonography of the knee with the “gold standard” of arthroscopy, as well as clinical examination, to validate ultrasonographic images in terms of accurate representation of the pathology present in the joint. They concluded that ultrasonography was valid and reproducible, as well as superior to clinical examination for detecting knee synovitis.

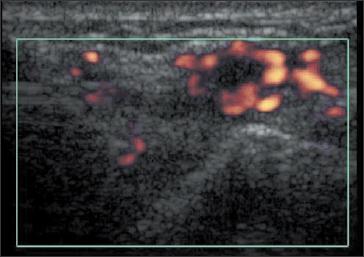

The development of power Doppler techniques to evaluate blood flow in the vascular synovium (indicating inflammatory activity) has enhanced the diagnostic power of ultrasonography (Figure 2).29,30 Early work also has been done on the use of echocontrast agents, which after injection may produce a qualitative increase in power Doppler signal from synovial vessels (the first sign of synovial changes in inflammatory disease), although use of such contrast media in clinical practice currently is not routine.

Figure 2 –

Synovitis of a patient’s ulnarcarpal joint is demonstrated in this ultrasonogram that includes power Doppler enhancement.

In Europe, ultrasonography remains a clinical tool for identifying subclinical synovitis and erosions in patients with negative radiographic results. It is also useful for monitoring response to various drug treatments. In the United States, the use of ultrasonography is less widespread and it is not available to many physicians in the office setting.

LOOKING INTO THE FUTURE

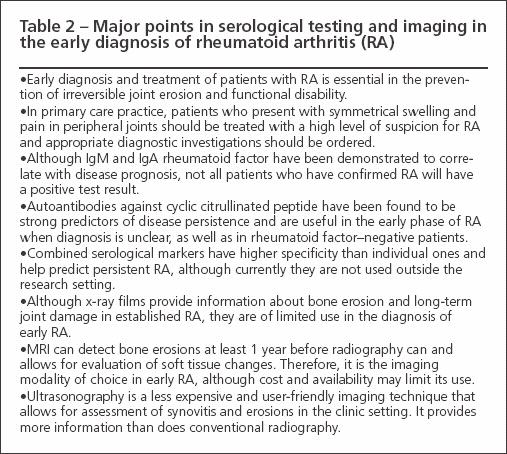

Spotting the early warning signs of RA involves both serological testing and imaging (Table 2). Currently, measuremen

t of RF combined with radiography is used most commonly. In the future, however, anti-CCP in combination with RF will play an increasing role in diagnosis and prognosis.

Within imaging, there will be a move from plain radiography to MRI, possibly with a significant role for low-field imaging. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography will be an alternative to MRI in centers that have easier access to it or as an adjunct.

22

The case can be made for MRI as the gold standard in RA assessment, with ultrasonography used as a “bedside tool” for improved joint evaluation (compared with clinical examination alone) and for better targeting of joint injections. Other imaging techniques that probably will become more available include positron emission tomography and quantitative CT.

References:

References

- 1. Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:649-655.

- 2. Chan KW, Felson DT, Yood RA, Walker AM. The lag time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:814-820.

- 3. Emery P. The Roche Rheumatology Prize Lecture: the optimal management of early rheumatoid disease: the key to preventing disability. Br J Rheum. 1994;33:765-768.

- 4. van Leeuwen MA, van Rijswijk MH, Sluiter WJ, et al. Individual relationship between progression of radiological damage and the acute phase response in early rheumatoid arthritis: towards development of a decision support system. J Rheum. 1997;24:20-27.

- 5. Gough AK, Lilley J, Eyre S, et al. Generalised bone loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1994;344:23-27.

- 6. Aho K, Palosuo T, Knekt P, et al. Serum C-reactive protein does not predict rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1136-1138.

- 7. Emery P. The Dunlop-Dottridge Lecture: prognosis in inflammatory arthritis: the value of HLA genotyping and the oncological analogy. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1436-1442.

- 8. Green M, Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D, et al. Persistence of mild, early inflammatory arthritis: the importance of disease duration, rheumatoid factor, and the shared epitope. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2184-2188.

- 9. van Zeben D, Hazes JM, Zwinderman AH, et al. Clinical significance of rheumatoid factors in early rheumatoid arthritis: results of a follow up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:1029-1035.

- 10. Gough A, Faint J, Salmon M, et al. Genetic typing of patients with inflammatory arthritis at presentation can be used to predict outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1166-1170.

- 11. Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:380-386.

- 12. Berglin E, Sundin U, Wadell G, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide before disease onset predict radiological outcome of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(suppl):S161.

- 13. van Gaalen FA, Linn-Rasker SP, van Venrooij WJ, et al. Autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides predict progression to rheumatoid arthritis in patients with undifferentiated arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:709-715.

- 14. Huang J, Stewart N, Crabbe J, et al. A 1-year follow-up study of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging in early rheumatoid arthritis reveals synovitis to be increased in shared epitope-positive patients and predictive of erosions at 1 year. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:407-416.

- 15. Raza K, Breese M, Nightingale P, et al. Predictive value of antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptide in patients with very early inflammatory arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:231-238.

- 16. Ostergaard M, Hansen M, Stoltenberg M, et al. New radiographic bone erosions in the wrists of patients with rheumatoid arthritis are detectable with magnetic resonance imaging a median of two years earlier. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2128-2131.

- 17. McGonagle D, Conaghan PG, O’Connor P, et al. The relationship between synovitis and bone changes in early untreated rheumatoid arthritis: a controlled magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1706-1711.

- 18. McQueen FM, Stewart N, Crabbe J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the wrist in early rheumatoid arthritis reveals progression of erosions despite clinical improvement. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:156-163.

- 19. Ostergaard M, Peterfy C, Conaghan P, et al. OMERACT Rheumatoid Arthritis Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies: core set of MRI acquisitions, joint pathology definitions, and the OMERACT RA-MRI scoring system. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1385-1386.

- 20. Ostergaard M, Klarlund M, Lassere M, et al. Interreader agreement in the assessment of magnetic resonance images of rheumatoid arthritis wrist and finger joints-an international multicenter study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1143-1150.

- 21. Ostendorf B, Peters R, Dann P, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and miniarthroscopy of metacarpophalangeal joints: sensitive detection of morphologic changes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2492-2502.

- 22. Ostergaard M, Szkudlarek M. Imaging in rheumatoid arthritis-why MRI and ultrasonography can no longer be ignored. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:63-73.

- 23. Taouli B, Zaim S, Peterfy CG, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis of the hand and wrist: comparison of three imaging techniques. AJR. 2004;182:937-943.

- 24. Lindegaard H, Vallo J, Horslev-Petersen K, et al. Low field dedicated magnetic resonance imaging in untreated rheumatoid arthritis of recent onset. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:770-776.

- 25. Wakefield RJ, Gibbon WW, Conaghan PG, et al. The value of sonography in the detection of bone erosions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison with conventional radiography. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2762-2770.

- 26. Hau M, Schultz H, Tony HP, et al. Evaluation of pannus and vascularization of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints in rheumatoid arthritis by high-resolution ultrasound (multidimensional linear array). Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2303-2308.

- 27. Kraan MC, Versendaal H, Jonker M, et al. Asymptomatic synovitis precedes clinically manifest arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1481-1488.

- 28. Karim Z, Wakefield RJ, Quinn M, et al. Validation and reproducibility of ultrasonography in the detection of synovitis in the knee: a comparison with arthroscopy and clinical examination. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:387-394.

- 29. Wakefield RJ, Brown AK, O’Connor PJ, Emery P. Power Doppler sonography: improving disease activity assessment in inflammatory musculoskeletal disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:285-288.

- 30. Wakefield RJ, Brown AK, O’Connor PJ, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography: what is it and should training be compulsory for rheumatologists? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:821-822.Â