Arm Pain, Weakness, and Bruising in an 82-Year-Old Homemaker

An 82-year-old right-handed woman, a homemaker, was evaluated for mild left upper arm pain, weakness, and bruising that had lasted for 4 days. Although she reported no previous history of rotator cuff injury or trauma per se, she did recall a sensation of "giving way" in the left upper arm while manually rolling up the driver's-side window in her car at the time of the initial event. Several hours later, a significant bruise appeared that extended from the middle of her upper arm toward the elbow, along with a mid-arm bulge that was more prominent with flexion. She denied having experienced an initial audible "pop," local corticosteroid injection, use of anticoagulants, or long-term fluoroquinolone treatment.

An 82-year-old right-handed woman, a homemaker, was evaluated for mild left upper arm pain, weakness, and bruising that had lasted for 4 days. Although she reported no previous history of rotator cuff injury or trauma per se, she did recall a sensation of "giving way" in the left upper arm while manually rolling up the driver's-side window in her car at the time of the initial event. Several hours later, a significant bruise appeared that extended from the middle of her upper arm toward the elbow, along with a mid-arm bulge that was more prominent with flexion. She denied having experienced an initial audible "pop," local corticosteroid injection, use of anticoagulants, or long-term fluoroquinolone treatment.

The woman's past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and stenosis of the lumbar spine. She also related a remote history of right breast cancer for which she was treated with lumpectomy, node dissection, and radiation therapy.

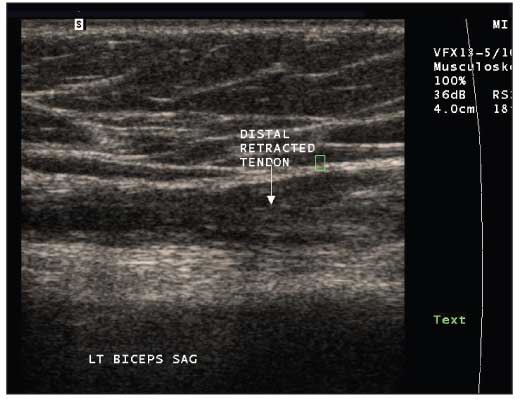

On examination of the patient's left anterior shoulder, there was tenderness and indentation over the bicipital groove. Left forearm flexion elicited pain and produced the mid-arm "ball" (photograph, above left); an area of ecchymosis extended from the bulging mass toward the elbow. An ultrasonogram of the patient's left shoulder was obtained to confirm the diagnosis (below left).

What does the ultrasonogram show?

What is your diagnosis? How would you treat this patient?

(Find the answer on the next page.)

The patient had a complete rupture of the long head of the biceps tendon. The diagnosis was strongly suspected on clinical grounds because the presentation included all the typical features of a biceps tendon rupture: pain, weakness on elbow flexion and forearm supination, ecchymosis, a bulging mass representing the distally retracted biceps muscle (often referred to as the "Popeye sign"), and even a history of straining on elbow flexion.

Localization of the rupture to the proximal biceps also is suggested clinically. A complete distal rupture would present with more profound weakness on elbow flexion, a more proximally located bulging mass, and a palpable defect in the distal biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa.1 Contrary to the presentation of distal rupture, patients with proximal rupture infrequently report antecedent trauma or an audible pop. Ruptures of the long head of the biceps are the result of degenerative changes within the tendon; older patients in particular are more likely to present with a gradual onset of pain.2,3 Other patients at risk for rupture of the long head of the biceps include those who have had local injections of steroids or have taken corticosteroids or anabolic steroids systemically, physical laborers, and middle-aged athletes who have experienced repeated trauma to the tendon resulting from overuse.

The ultrasonogram showed a ruptured long head of the biceps with marked distal retraction and age-related atrophy of the muscle belly of the long head. Aside from mild calcific tendinosis of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, no rotator cuff or joint abnormalities were noted.

The use of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of complete proximal biceps tears has been validated as highly sensitive (96%) and specific (100%), although ultrasonography is less reliable in the diagnosis of incomplete rupture.4 Given its low cost and excellent safety profile, ultrasonography is an ideal first imaging study, especially in older patients who have multiple comorbidities and when, as in this case, a complete tendon rupture is suspected. When the use of ultrasonography does not detect a complete tear, MRI is the follow-up imaging modality of choice to further evaluate a possible incomplete tear, especially in patients for whom corrective surgery would be considered.

There are 2 options for the treatment of patients with complete proximal biceps tendon rupture: conservative management and surgery. Conservative approaches include analgesics, NSAIDs/cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors, icing, and range of motion and gentle strengthening exercises. A return to full range of motion is expected by 6 to 8 weeks. Resumption of all activities of daily living should be anticipated in the 10- to 12-week time frame.

Surgical treatment is most often used with tenodesis of the biceps tendon to the proximal humerus. Proximal ruptures of the biceps historically have been managed conservatively much more often than distal ruptures; surgery has been reserved for younger persons who require significant biceps strength for recreational sports or work. More recently, it has been argued that a wider group of patients would benefit from surgery for a ruptured proximal biceps tendon; studies cited a loss of strength of 21% in supination and 8% in elbow flexion in patients who received conservative therapy compared with no lost strength in patients who underwent surgery.3,5

Our patient was treated with ice to control swelling and rest using sling immobilization and limitation of activity. Exercises to improve strength and flexibility were started several days later. The patient made an uneventful recovery and resumed full activities of daily living at 10 weeks.

This case was submitted by James S. Studdiford III, MD, clinical associate professor in the department of family medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, in Philadelphia; Caroline D. Fosnot, DO, staff physician in the department of medicine at Nazareth Hospital in Philadelphia; Rebecca S. Bernstein, a medical student at Jefferson Medical College; and Amber Stonehouse Tully, MD, assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College. (Clinical photograph published with permission from the Jefferson Clinical Image Database.)

References:

1. Sellards R, Kuebrich C. The elbow: diagnosis and treatment of common injuries. Prim Care. 2005;32:1-16.

2. Ozçakar L, Vanderstraeten G, Parlevliet T. Sonography and visualizing rotator cuff injuries in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1840-1841.

3. Schöffl VR, Harrer J, Küpper T. Biceps tendon ruptures in rock climbers. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:426-427.

4. Armstrong A, Teefey SA, Wu T, et al. The efficacy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of long head of the biceps tendon pathology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:7-11.

5. Mariani EM, Cofield RH, Askew LJ, et al. Rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;228:233-239.