Geographic & Racial Disparities Found in Reported US Amyloidosis Mortality

The lack of higher reported mortality rates in states with a greater proportion of black residents suggests underdiagnosis of amyloidosis, including cardiac forms of the disease, in many areas of the United States.

An observational cohort study published in JAMA Cardiology has revealed geographic disparities in reported amyloidosis mortality in the United States and suggests that the rare disease is underdiagnosed in many areas of the country.

Known to most commonly affect the heart, systemic amyloidosis continues to be underdiagnosed, and if left untreated, cardiac forms of the disease are highly fatal. As the majority of amyloidosis mortality is caused by cardiac involvement, the investigators turned to death certificate data to shed light on the epidemiology of amyloidosis.

For their analysis, which they report to be the largest and most racially diverse epidemiological data on reported US amyloidosis deaths to date, the investigators set out to explore trends in amyloidosis mortality reported in the United States from 1979 to 2015 and identify potential regions of the country where the disease might be under-detected.

Looking at death certificate data from 1979 to 2015 collected from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-ranging ONline Data for Epidemiologic Research database, the investigators found that during that time period, a total of 30764 individuals in the United States had amyloidosis listed as their underlying cause of death, while 25591 individuals had the disease listed as a contributing cause of death.

Of the 30764 individuals with amyloidosis as the underlying cause of death, 17421 (56.6%) were men and 27312 (88.8%) were 55 years of age or older. The number of amyloidosis deaths was reported to have increased from just 367 in 1979 to 1454 in 2015. As such, the age-adjusted amyloidosis death rate doubled during that time period, going from 1.77 per 1 000 000 (95% CI, 1.58-1.95) in 1979 to 3.96 per 1 000 000 (95% CI, 3.75-4.17) in 2015.

From 1999 to 2015, black men had the highest reported age-adjusted mortality rate at 12.36 per 1 000 000 (95% CI, 11.85-12.87), which investigators found to be almost double the rate observed for white men, which was 6.20 per 1 000 000 (95% CI, 6.09-6.31). Black women were found to have the second highest mortality rate at 6.48 per 1 000 000 (95% CI, 6.19-6.77).

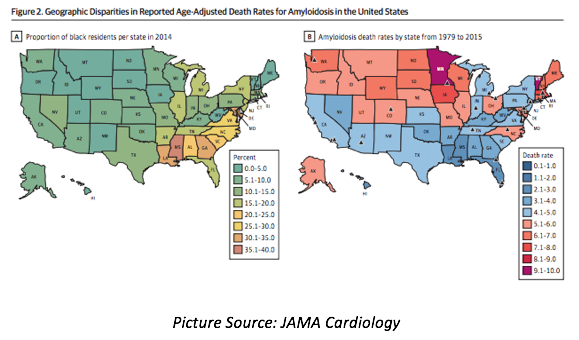

Investigators noted that although the majority of states reported an increased amyloidosis mortality rate over time, interstate differences were apparent. Of all 50 states, the investigators found that the mortality rate was highest in Minnesota from 1979 to 1998 compared with the national mean, but from 1999 to 2015, Vermont reported the highest rate. Interestingly, the investigators report that although many of the southern states had the highest proportion of black individuals residing in those regions, the lowest mortality rates were reported there.

When they evaluated county data for amyloidosis as a contributing cause of death, they found that the 5 counties that reported the highest amyloidosis mortality were located near amyloidosis referral centers. In fact, the first and third highest mortality rates were reported in areas close to Rochester, Minnesota, and Boston, Massachusetts, where Mayo Clinic and Boston University are located.

“The increased reported mortality over time and in proximity to amyloidosis centers more likely reflects an overall increase in disease diagnosis rather than increased lethality,” authors of the report write. They postulate that their findings indicate an underdiagnosis of amyloidosis in areas with less access to specialized care for the disease.

Furthermore, they add that consistent with previous research, black individuals were found to be overrepresented in amyloidosis mortality. Therefore, it would make sense that areas more heavily populated with black residents, such as the southern region of the United States, would have higher amyloidosis mortality rates. “Our contrary finding suggests that underdiagnosis is present,” the authors stress.

Future research is needed to glean a better understanding of geographic and racial disparity in the reporting of amyloidosis deaths, the authors conclude.