Steps to Minimize Serious Risks of Biologic Treatment for Autoimmune Disease

Although tumor necrosis factor inhibitors have dramatically improved management strategies for autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, the biologic agents also pose a number of significant side effects that physicians must consider.

Although tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have dramatically improved management strategies for autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the biologic agents also pose a number of significant side effects that physicians must consider.

To help internists navigate and avoid such safety concerns, a team of 4 researchers from the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh, PA, extensively reviewed the adverse effects of available anti-TNF therapies and provided steps to reduce those risks.

Prior to initiating anti-TNF agents like etanercept or infliximab, Jennifer Hadam, MD, and her colleagues advised internists to take a focused clinical history, bring age-appropriate vaccinations up to date, screen for tuberculosis and hepatitis B, and perform a full physical examination “with special attention to skin rashes ... (that) may serve as a baseline to assist with early detection of new rashes associated with anti-TNF therapy,” they wrote in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

After gathering that key information, the reviewers recommended remaining alert about the noninfectious complications of TNF inhibitors, which include injection site reactions that are common with subcutaneous agents, infusion reactions caused by infliximab, and paradoxical autoimmune conditions that “range from asymptomatic immunologic alterations … to life-threatening systemic autoimmune diseases,” they noted.

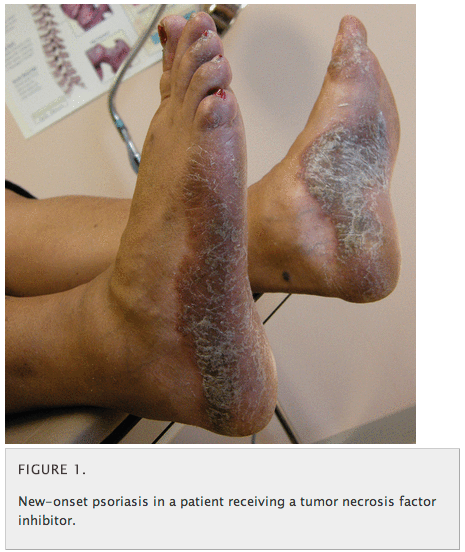

“Interestingly, anti-TNF agents are approved for treating psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, but psoriasis has paradoxically developed in patients being treated with these drugs for other autoimmune diseases (Figure 1),” the authors warned. “Autoimmune diseases associated with anti-TNF treatment include a lupus-like syndrome, vasculitides, and psoriatic skin lesions. These syndromes warrant stopping the inciting drug and, on occasion, giving corticosteroids.”

Additionally, the researchers said studies have shown patients taking TNF inhibitors can experience cardiovascular side effects — “from nonspecific and asymptomatic arrhythmias to worsening of heart failure” — and the onset or exacerbation of central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating disorders, including multiple sclerosis (MS). In response to those serious risks, they noted anti-TNF therapy is “contraindicated in patients with NYHA class III or IV heart failure” and “should not be initiated in patients who have a history of demyelinating disease.”

While clinical evidence on the risk of malignancies like non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and skin cancer with the use of TNF inhibitors is mixed, the review authors said the therapies do increase the risk of infections “ranging from minor to life-threatening bacterial infections, and including the reactivation of granulomatous and fungal infections.” As a result, “TNF inhibitors must be held in the event of a major infection … (and) consultation with an infectious disease specialist is recommended, especially in complex cases,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, Hadam and her colleagues noted the benefits of managing autoimmune diseases with appropriate anti-TNF therapies far outweigh the risks described in their review, though they also emphasized that “physicians must be aware of atypical presentations of infection and understand how their treatment may differ in patients on biologic therapy.”