Paclitaxel-Eluting Balloons, Paclitaxel- Eluting Stents, and Balloon Angioplasty in Patients With Restenosis After Implantation of a Drug-Eluting Stent

Hitinder S. Gurm, MD

Review

Byrne RA, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, et al for the ISAR-DESIRE 3 investigators. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and balloon angioplasty in patients with restenosis after implantation of a drug-eluting stent (ISAR-DESIRE 3): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2013;381:461-467.

Since the early days of coronary angioplasty, coronary restenosis has been the biggest limitation of the procedure, and intense research has been focused on minimizing restenosis.1 Coronary restenosis in bare metals stents (BMS) was a common problem, and a large body of research focused on strategies to prevent and treat bare metal stent restenosis. The advent of drug-eluting stents (DES) and their widespread adoption has markedly reduced the clinical burden of restenosis. Although drug-eluting stents have demonstrated remarkable efficacy at reducing restenosis, the complication has not been eliminated, and clinically relevant restenosis is seen in approximately 5% of patients treated with drug-eluting stents.2,3 While significant randomized and observational data exist for treatment of BMS restenosis, DES restenosis has received less scrutiny.4,5

The treatment of DES restenosis remains a challenge and the ISAR-DESIRE 3 study provides some welcome guidance on optimal treatment of these patients.6

Study Details

The ISAR-DESIRE 3 was a randomized controlled trial that enrolled patients with restenosis of at least 50% impacting a limus-eluting stent at 3 centers in Germany. Patients were randomly assigned to treatment with a paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES), paclitaxel-eluting balloon (PEB), or balloon angioplasty in an open-label fashion. Randomization was stratified in a 1:1:1 fashion by center. PEB catheters were coated with 3 μg of paclitaxel per mm² of balloon surface with iopromide as hydrophilic spacer (length, 10-30 mm; diameter, 2.5-4.0 mm). The patients and investigators were not masked to treatment allocation but end point ascertainment and angiograms were assessed by blinded investigators.

The primary end point was diameter stenosis at follow-up angiography at 6 to 8 months. Primary analysis was done by intention to treat. Patients were excluded if they had a target lesion located in the left main stem or in a coronary bypass graft, acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, severe renal insufficiency, a comorbid condition with life expectancies of less than 12 months, or contraindications or known allergy to antiplatelet therapy, paclitaxel, or stainless steel. The same randomly assigned treatment approach had to be used for all restenotic lesions in patients who required treatment of more than 1 restenotic lesion. The use of more than 1 balloon or stent per lesion was allowed. Stenting was strongly discouraged in the groups assigned to PEB or balloon angioplasty but could be used for bailout in the event of residual stenosis of >50% or a flow-limiting dissection.

The study enrolled 402 patients, of whom 137 (34%) were assigned to PEB, 131 (33%) to PES, and 134 (33%) to balloon angioplasty. A total of 42% of the cohort had diabetes mellitus and most (67%) of the lesions had a focal restenotic pattern. A total of 500 lesions were treated in the study. The proportion of patients treated per protocol did not differ between groups. There were 11 lesions in the PEB group being treated with stent implantation (6 with PES, 1 with a BMS, and 4 with everolimus-eluting stents), 12 lesions in the PES group were treated with balloon dilatation only (2 with PEB), and 10 lesions in the balloon angioplasty group were treated with DES

implantation. Follow-up angiography was available for 338 (84%) patients.

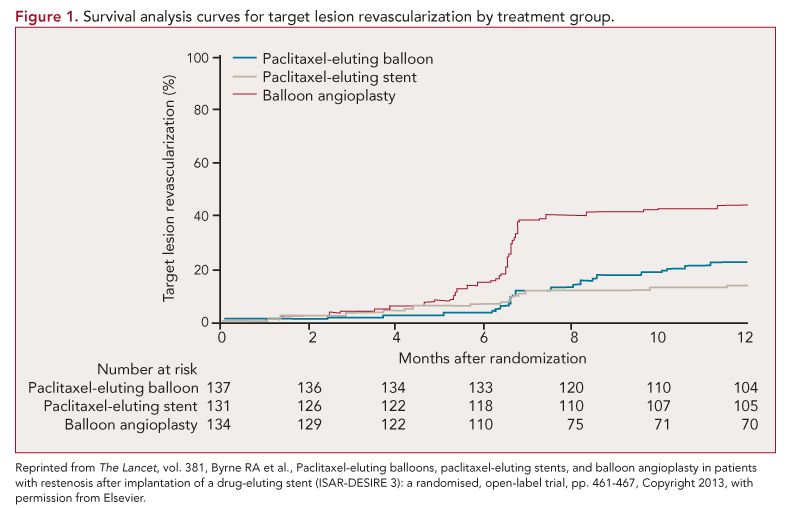

PEB was non-inferior to PES for the primary end point of diameter stenosis (38.0% vs 37.4%; difference 0.6%, 1-sided 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.9%; Pnon-inferiority = 0.007; non-inferiority margin of 7%). Findings were consistent in per-protocol analysis. PEB and PES were superior to balloon angioplasty alone (54.1%; Standard Deviation, 25.0]; Psuperiority<0.0001 for both comparisons). The results were consistent across multiple prespecified subgroups including age, sex, diabetes, and vessel size. There was no difference in the frequency of death, myocardial infarction, or target lesion thrombosis between the 3 groups. Significant differences were noted with respect to target vessel revascularization (TVR: 24.2% with PEB vs 16.6% with PES vs 45.1% with angioplasty only) and target lesion revascularization (22.1% with PEB vs 13.5% with PES vs 43.5% with angioplasty only) (Figure 1).

References

1. Moliterno DJ. Healing Achilles--sirolimus versus paclitaxel. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:724- 727.

2. Gurm HS, Boyden T, Welch KB. Comparative safety and efficacy of a sirolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stent: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;155:630-639.

3. Wessely R, Kastrati A, Schomig A. Late restenosis in patients receiving a polymer-coated sirolimus-eluting stent. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:392-394.

4. Alfonso F, Perez-Vizcayno MJ, Hernandez R, et al. A randomized comparison of sirolimus-eluting stent with balloon angioplasty in patients with in-stent restenosis: results of the Restenosis Intrastent: Balloon Angioplasty Versus Elective Sirolimus-Eluting Stenting (RIBS-II) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2152-2160.

5. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, von Beckerath N, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stent or paclitaxel-eluting stent vs balloon angioplasty for prevention of recurrences in patients with coronary instent restenosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:165-171.

6. Byrne RA, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and balloon angioplasty in patients with restenosis after implantation of a drug-eluting stent (ISAR-DESIRE 3): a randomised, openlabel trial. Lancet. 2013;381:461-467.

7. Stone GW, Ellis SG, O’Shaughnessy CD, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents vs vascular brachytherapy for in-stent restenosis within baremetal stents: the TAXUS V ISR randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1253-1263.

8. Kastrati A, Byrne R. New roads, new ruts: lessons from drug-eluting stent restenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:165-167.

9. Cosgrave J, Melzi G, Biondi-Zoccai GG, et al. Drug-eluting stent restenosis the pattern predicts the outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2399-2404.

10. Fujii K, Mintz GS, Kobayashi Y, et al. Contribution of stent underexpansion to recurrence after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for in-stent restenosis. Circulation. 2004;109:1085-1088.

11. Cosgrave J, Melzi G, Corbett S, et al. Repeated drug-eluting stent implantation for drug-eluting stent restenosis: the same or a different stent. Am Heart J. 2007;153:354-359.

12. Alfonso F. Treatment of drug-eluting stent restenosis the new pilgrimage: quo vadis? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2717-2720.

13. Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W, et al. Treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2113-2124.

Commentary The Challenge of Treating DES Restenosis

Drug-eluting stents are the dominant treatment for patients undergoing PCI and have demonstrated consistent superiority over other strategies for both de novo and restenotic lesions.7 In patients with restenosis following implantation of BMS, DES use is superior to brachytherapy or angioplasty only. Given the widespread use of DES in clinical practice, DES restenosis, even though uncommon, is probably more frequently encountered in clinical practice compared with BMS restenosis.8

DES restenosis is a heterogeneous disorder and differs from BMS restenosis in its temporal and morphological presentation as well as in the underlying pathophysiology. The focal restenotic pattern is most commonly seen with limuseluting stents.9 Stent underexpansion and stent fracture have been causally invoked in a significant proportion of DES restenosis cases.10 Drug resistance or failure remains another possible concern.

Treatment of DES restenosis has clinically been a greater challenge compared with BMS restenosis. Observational studies have demonstrated a higher rate of restenosis and a greater need for repeat revascularization. Treatment of DES restenosis has traditionally involved the use of a limus-eluting stent for a PES restenosis and a PES-eluting stent for a limus restenosis. While intuitively appealing, this strategy has been poorly studied, and the few studies that have been performed have produced mixed results.11 Furthermore, there is concern that a DES within a DES would increase the risk of stent thrombosis, although this has not yet been clearly demonstrated.12

Nevertheless, the use of a DES within a DES for DES restenosis, while commonly practiced, is somewhat unsatisfactory and the current study provides the evidence base to support the use of PEB for this recalcitrant problem. The PEB was associated with a late loss that was similar to PES, and the overall restenosis rates were no different, suggesting that PEB may well be the preferred initial strategy for these patients. Despite the lack of difference in restenosis, a significant difference in TVR was noted. The Kaplan-Meier curves for TVR for the 3 strategies start to diverge at the 6-month time point, suggesting that the mandatory angiographic follow-up and the oculo- stenotic reflex may have influenced the operators to intervene for lesions that may or may not have been clinically symptomatic. It is also likely that the operators were less likely to intervene in patients who had already been treated with a PES for their in-stent restenosis (ISR).

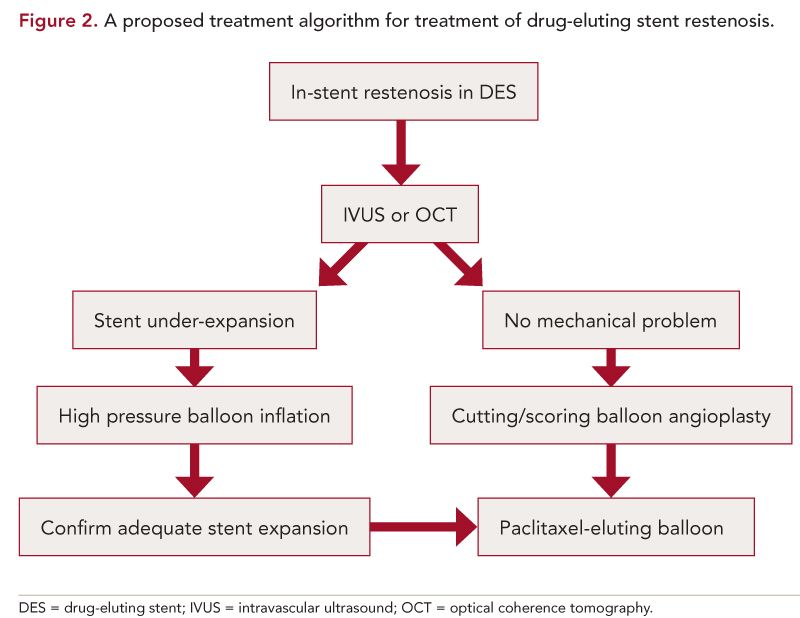

The PEB has demonstrated excellent efficacy in patients with BMS restenosis, as well as for treatment of peripheral arterial disease, and the results of this study suggest that it may be the ideal treatment for DES restenosis.13 While it is always desirable to have more randomized data, preferably with purely clinical follow-up, it is unlikely that we will see a study like that soon. Currently, our approach to DES restenosis involves imaging using intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography followed by high pressure balloon dilation if stent underexpansion is identified. Otherwise we implant a PES for restenosis in a limus-eluting stent and vice versa (although PES restenosis is uncommonly encountered due to infrequent use of PES in contemporary practice). The PEB is not currently available in the United States but it is likely that our approach to DES ISR will probably change to the schema outlined in Figure 2 once they are clinically approved.

Although there are no randomized data to support use of scoring devices in DES restenosis, it is likely that pretreatment with these devices will prevent melon-seeding of the PEB and help ensure optimal drug delivery and enhance device efficacy.

The PEB has demonstrated remarkable efficacy and is a welcome addition to the catheterization laboratory armamentarium. Once clinically available, it will likely emerge as the preferred device for both DES and BMS restenosis.

About the Author

Hitinder S. Gurm, MD , is Associate Professor, Director of Inpatient Cardiology Services, and Director of Carotid Interventions in Cardiovascular Medicine in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Michigan Cardiovascular Center in Ann Arbor. He received his MD from Christian Medical College in Ludhiana, India, and completed his Residency and Fellowships at Cleveland Clinic Foundation. His research interests include outcomes research and quality improvement in percutaneous coronary and peripheral interventions and endovascular therapy of carotid disease. He is the principal investigator of the Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Collaborative (BMC2), a statewide registry focused on improving safety and appropriateness of PCI across all hospitals in the state of Michigan.