Publication

Article

Romania's Recaptured and Restored Capital

Author(s):

Once called "the Paris of the East," Bucharest still shows signs of the vast and permanent destructive changes wrought on the city by despised despot Nicolae Ceausescu.

Photography by the authors

How does a European country recapture its capital and from whom? Franks, Vandals, Huns? No, those were the barbarians of earlier centuries and the Dark Ages ended about 800 AD.

The communist criminal from whom the people of Romania finally wrenched its “Lost City,” Bucharest, was more rapacious than any Visigoth tribe that ever crossed their land. It was the despised (and possibly demented) despot, Nicolae Ceausescu. When he and his wife were arrested and shot by a firing squad on December 25, 1989, it was surely a Christmas present to the Romanian people.

In Bucharest we drive into Revolutionary Square with its 2005 Memorial of Rebirth. The controversial column has been ridiculed as an Olive on a Toothpick or a Potato on a Stake and as not adequately representing the 1,500 people who suffered and died in the revolution needed to bring down Ceausescu.

The monstrosity originally called The Palace of the People (now the Palace of the Parliament) is said to be the largest parliament building in the world. It has become a national government office, perfect for politicians with the usual bloated sense of their own importance.

Those standing on the balcony of the palace can look down the avenue Ceausescu deliberately made wider than the Champs-Élysées in Paris as he destroyed most of historic Bucharest. It is the same balcony from which Michael Jackson looked down on his local admirers and shouted, “Hello, Budapest!”

Inside the palace is stark marble: no money was left for furniture and Ceausescu was executed before it was finished.

Ceausescu’s largesse with his people’s money and the communist regime probably set Romania back 44 years (if you count from the end of World War II in 1945 to the People’s Revolution in 1989). The extraordinary megalomania of Ceausescu may have done even more damage because his power lust (which he thought was vision) made vast destructive changes to his capital.

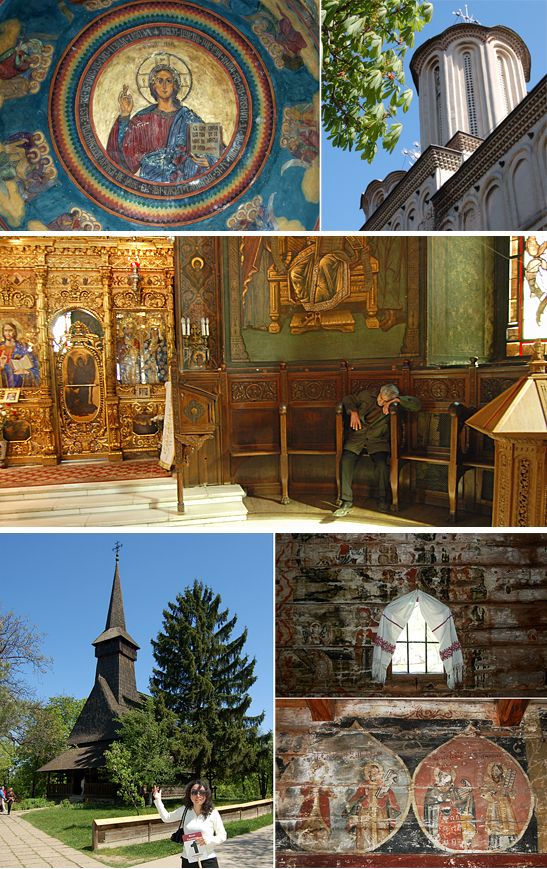

Top and middle rows: The Patriarchal Cathedral. Bottom row: Church in the Bucharest National Village Museum.

It wouldn’t be a European vacation without seeing more than our share of churches. The striking thing about them is that some are so large and so over-decorated by North American standards. While many interiors are in poor repair, there are no obvious enthusiasts with collecting cans asking for help to restore the churches.

Such apathy may be because the country is still poor and the communists who were so anti-church have left their mark. After all it was Karl Marx who said religion is the opium of the people.

A less flamboyant church is the delightful and small Stavropoleos Church, built on the edge of what is now Old Town in 1724 by a Greek monk. The Stavropoleos interior is exquisite—a surprise, because the outside is not particularly striking.

St. Nicholas Church has a more upscale history. It was created in 1905-1909 thanks to a 600,000 gold ruble donation from a Russian: the tsar, himself.

Tsar Alexander II approved the 7 Russian onion domes on top and the iconostasis below that is reputedly a reproduction of the altar in one of the cathedrals in the Kremlin.

We get directions from our guide and head for the 16-room hotel, the Rembrandt that we had booked online. It is a great choice: simple, clean and conveniently located in the Old Town. It was also inexpensive. At the time of our stay we paid $160 a night.

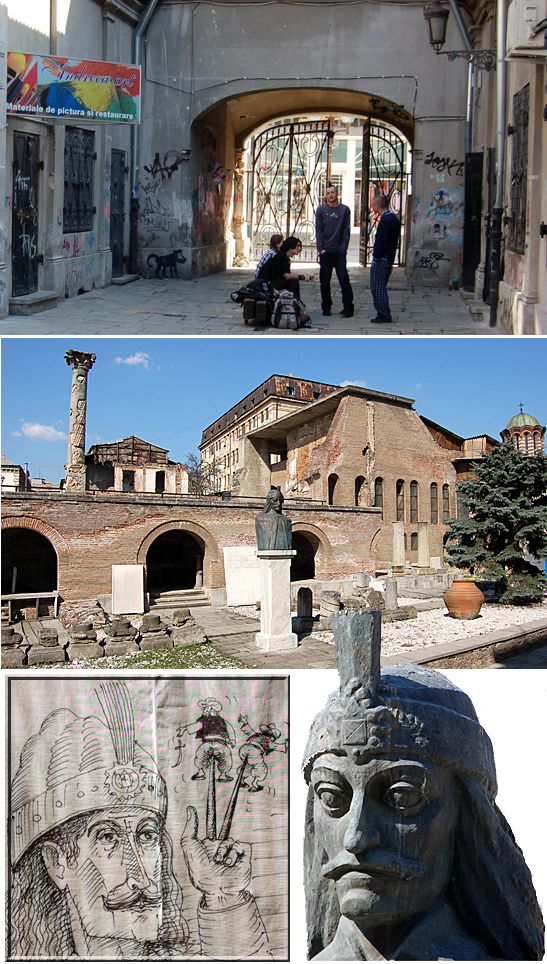

The next day we walk with a street map of the city. Our destination has been marked by the hotel: Curtea Veche (the Old Court). We wander past alleys with ancient gates, along deserted streets as quiet as a Sunday and come, at the end of Strada Franceză, to the ruined walls of the Old Princely Court.

The prince of Wallachia, who built the Prince’s Palace in the 15th century at the apogee of his powers, is someone not seen as a prince by his enemies—and he had many in the Ottoman Empire. His successors later increased fortifications, but by the 18th century, after an earthquake and a fire, the palace had fallen into ruin. A museum was established here in 1972.

The best records of this Palace of the Wallachian Princes were those dated September 20, 1459, by Prince Vlad III. His bust stands on a pedestal outside as if guarding the ruins. He is the most famous of the Princes Vlad.

Prince Vlad II was chosen as a member of the Holy Roman Empire’s secret society “to uphold Christianity, the Order of the Dragon.” The Romanian word for dragon is “drac” and the definitive is “ul.” So dracul meant “the dragon” and the “a” at the end is the diminutive. Thus, the name used by his son, Vlad III, was Vlad Dracula: the little dragon. He also used Vlad Tepes, but especially enjoyed being called Vlad the Impaler.

A student who spoke some English walks past as we take some photographs, hears our conversation, and directs our attention to a poster on a wall.

“The drawing is not realistic,” he says. “Vlad did not limit himself to just 2; he impaled thousands, but most were Ottomans!”

It is surely not a children’s bedtime story.

The Andersons, who live in San Diego, are the resident travel & cruise columnists for Physician's Money Digest. Nancy is a former nursing educator, Eric a retired MD. The one-time president of the NH Academy of Family Practice, Eric is the only physician in the Society of American Travel Writers. He has also written five books, the last called The Man Who Cried Orange: Stories from a Doctor's Life.