State-mandated CME Is Well-intentioned but Flawed

Continuing medical education is far too important an endeavor to be subjected to a political process, especially one that is often driven by news headlines or the personal experiences of legislators or influential constituents.

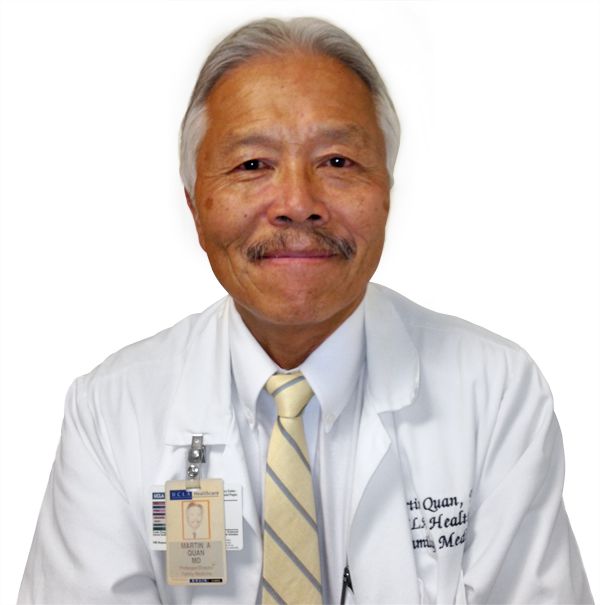

Marin Quan, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Much to the consternation of physicians in the state of Connecticut, the 2013 session of the General Assembly passed a bill that expanded the mandated continuing medical education (CME) requirements for licensure.

This new law, which went into effect on July 1, 2013, requires physicians to complete one contact hour of qualifying CME in the subject area of behavioral health within 24 months. However, this legislative intrusion into CME was not without precedent. The bill amended the Connecticut General Statute Section 20-10b, which now stipulates that physicians must complete a minimum of 50 contact hours of CME every 2 years, including at least one contact hour of training or education in infectious diseases, risk management, sexual assault, domestic violence, cultural competency, and behavioral health.

By no means is Connecticut the only state where legislators tell physicians what they have to learn. In fact, 17 other states also specify subject areas doctors must study as part of their CME requirements. For example, California mandates that all physicians except pathologists and radiologists must complete 12 CME units on pain management and the appropriate care and treatment of the terminally ill, while geriatric medicine must comprise 20% of the mandatory CME for general internists and family physicians, since more than 25% of their patient population is over 65 years of age.

Over the past few years, a growing number of states have enacted statutes, rules, or regulations that require physicians to earn CME units directed at appropriately prescribing controlled substances. This requirement now exists in Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Vermont, and West Virginia, and it is on the drawing board in Delaware and New York. Other topics that fall into the category of state-mandated CME include cultural competency, medical ethics, HIV infections, domestic violence, patient safety, child abuse, dependent adult abuse, and pain management.

Although one would be hard-pressed to argue against the relevance and appropriateness of these subject areas, objections can be raised on subjecting physician education to the political process.

Since the first conceptualization of CME by the American Academy of General Practice (AAGP) in 1947, physicians have traditionally engaged in "self-directed learning” based on practice reflection, deciding for themselves what courses and content areas best meet the needs of their patients and practices. In 2004, the concept of "directed self-learning” was introduced to family physicians by the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) within the framework of maintenance of certification (MOC) programs, particularly its part II activities, which are more commonly referred to as self-assessment modules (SAMs). These modules effectively served to direct diplomates’ CME focus to areas of practice where important performance gaps were determined to exist by the Institute of Medicine (IOM).

The medical profession has proven itself more than capable of fulfilling its social contract to develop and maintain standards for competent service provided by its members. CME is far too important an endeavor to be subjected to a political process, especially one that is often driven by news headlines or the personal experiences of legislators or influential constituents.

Martin Quan, MD

Editor-in-Chief

Martin Quan, MD, is Professor of Clinical Family Medicine and Director of the Office of Continuing Medical Education at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. He is also a member of the Education Advisory Board and consultant to the Committee on Continued Professional Development of the California Academy of Family Physicians and a member of the Kidney Learning System Advisory Board of the National Kidney Foundation. In the past, Quan has served as Program Director of the UCLA Family Practice Residency Program, Co-Director of the UCLA Pre-Doctoral Program in Family Practice, Editor-in-Chief of Clinical Cornerstone, and Vice Chair of the Residency Review Committee in Family Practice for the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).