Strategies for Multivessel Revascularization in Patients with Diabetes

Sachin S. Goel, MD

and Mehdi H. Shishehbor, DO, MPH

Review

Patients with diabetes mellitus constitute up to 25% of all patients undergoing coronary revascularization.1 These individuals often have complex multivessel coronary artery disease, and their procedural and long-term risk is higher after coronary revascularization compared with those without diabetes.2 It is known from the BARI (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation) trial that patients with diabetes and multivessel disease who undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery have survival benefit at 5 and 10 years, compared with those undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using balloon angioplasty alone.3,4

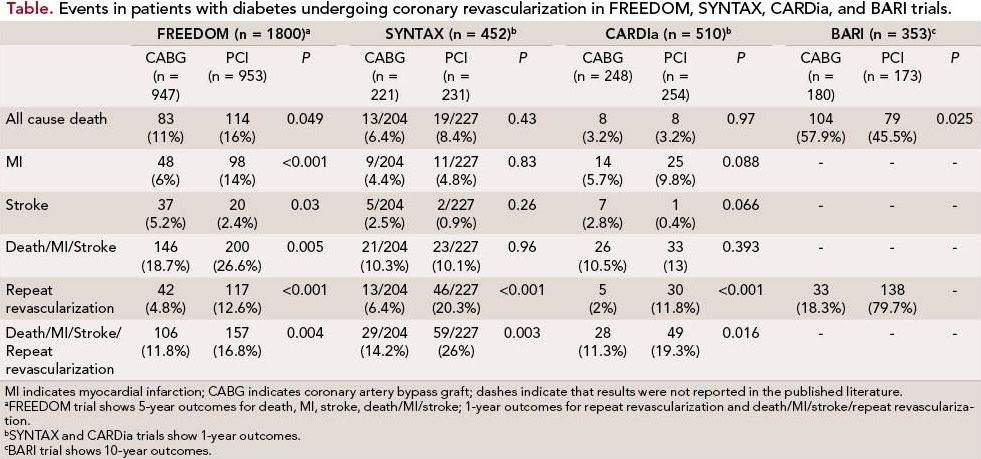

Over the last 2 decades, CABG (with the use of internal mammary grafts) and PCI (with the use of drug-eluting stents) have evolved significantly. Additionally, medical therapies for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes have also significantly advanced. Despite earlier data favoring CABG surgery over PCI, many believed that drug-eluting stents may have balanced the risk and benefit between these 2 procedures among this high-risk population. However, the recent CARDia (Coronary Artery Revascularization in Diabetes) trial and a subgroup analysis of the SYNTAX (Synergy Between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) trial both showed an increased rate of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events at 12 months for patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary disease who underwent PCI compared with CABG, but both studies were underpowered.5-7 The FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease) trial was designed to address some of these issues using appropriate sample size and contemporary techniques and technology.

Study Details

In the NHLBI-sponsored randomized prospective FREEDOM trial, investigators sought to evaluate whether coronary revascularization with CABG or PCI with drug-eluting stents is superior in patients with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease, defined as coronary stenosis >70% in 2 or more major epicardial vessels involving at least 2 separate coronary territories. Main exclusion criteria included severe left main coronary artery stenosis (≥50%), class III or IV congestive heart failure, and prior CABG or valve surgery. Between 2005 and 2010, 32,966 patients were screened to identify 3309 trial-eligible patients, of whom 1900 consented and underwent randomization (953 and 947 patients to PCI and CABG, respectively). The mean age was 63 years and the mean A1C was 7.8% in both groups. Less than a third of patients were on insulin in both groups. The majority of patients had preserved left ventricular function; more than 80% of patients had 3-vessel coronary disease; however, the mean SYNTAX score was 26. In the PCI group, sirolimus and paclitaxel-eluting stents were used in 51% and 43% of patients, respectively. Dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended for at least 12 months, and patients were followed for a minimum of 2 years, with a median follow-up of 3.8 years.

The primary outcome—a composite of allcause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), or nonfatal stroke—occurred less frequently in the CABG group compared with those undergoing PCI (5-year rates of 18.7% vs 26.6%, P = 0.005), indicating an absolute risk reduction of 7.9% and relative risk reduction of 30% with CABG. Coronary bypass surgery was also associated with significant reduction in all-cause mortality (10.9% vs 16.3%, P = 0.049) and MI (6% vs 13.9%, P <0.0001) compared with PCI. In contrast, stroke occurred more frequently in the CABG group (5.2% vs 2.4%, P = 0.03). At 1 year, the rates of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events were significantly higher in the PCI group compared with the CABG group (16.8% vs 11.8%, P = 0.004), with this difference largely attributable to higher repeat revascularization rates in the PCI group (12.6% vs 4.8%, P <0.001). CABG was superior to PCI across all pre-specified subgroups, including across complexity of coronary artery disease as indicated by the tertiles of SYNTAX score, with higher event rates in patients undergoing PCI compared with CABG for those with SYNTAX scores of <22 (23.2% vs 17.2%), 23 to 32 (27.2% vs 17.7%), and >33 (30.6% vs 22.8%).

References

1. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

2. Flaherty JD, Davidson CJ. Diabetes and coronary revascularization. JAMA. 2005;293:1501- 1508.

3. The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) Investigators. Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with angioplasty in patients with multivessel disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:217-225.

4. The final 10-year follow-up results from the BARI randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1600-1606.

5. Kapur A, Hall RJ, Malik IS, et al. Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with coronary artery bypass grafting in diabetic patients: 1-year results of the CARDia (Coronary Artery Revascularization in Diabetes) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:432-440.

6. Banning AP, Westaby S, Morice MC, et al. Diabetic and nondiabetic patients with left main and/ or 3-vessel coronary artery disease: comparison of outcomes with cardiac surgery and paclitaxel-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1067-1075.

7. Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360: 961-972.

8. Serruys PW, Ong AT, van Herwerden LA, et al. Five-year outcomes after coronary stenting versus bypass surgery for the treatment of multivessel disease: the final analysis of the Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study (ARTS) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:575-581.

9. Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, et al. Everolimus- eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1663- 1674.

10. Serruys PW, Silber S, Garg S, et al. Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and everolimus-eluting coronary stents. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:136-146.

Commentary A Landmark Study of CABG Versus PCI

The FREEDOM trial is a landmark trial that confirms the significant benefit of CABG over PCI with drug-eluting stents in patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease. The benefits of CABG over PCI in prior studies such as ARTS (Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study), the CARDia trial, and the subgroup analysis of the SYNTAX trial were mainly driven by reduction in repeat revascularization with CABG compared with PCI.5,6,8 However, in the FREEDOM trial, the benefit of CABG over PCI in those with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease was driven by reduction in allcause mortality and MI.

From the BARI trial to the FREEDOM trial, despite refinements in PCI from balloon angioplasty to drugeluting stents, the survival benefits of CABG in patients with diabetes appear to have stood the test of time. This is a key finding that has the potential to significantly change clinical practice and strengthen current recommendations in the guidelines for management of diabetic patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. In addition, the benefits of CABG were sustained over the tertiles of SYNTAX score, indicating that CABG leads to superior outcomes despite varying complexity of coronary artery disease.

However, despite its importance and potential clinical impact, the FREEDOM trial has several limitations. Even though all-cause mortality and MI favored CABG, stroke risk was higher in the CABG group, mainly driven by excess postoperative strokes in the 30 days after CABG. Additionally, the rates of cardiovascular deaths (64% of all deaths) did not differ between CABG and PCI. Furthermore, the overall study population is low risk with a mean left ventricular ejection fraction of 66% and a mean EuroSCORE of 2.8% in the CABG arm. Indeed, a majority of patients had SYNTAX scores in the low or intermediate tertiles. These findings raise concern about the applicability of the findings from the FREEDOM trial to higher-risk patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease. Furthermore, only 10% of patients screened were deemed trialeligible for FREEDOM, raising questions about the overall generalizability of the FREEDOM trial.

The median followup in the FREEDOM trial was 3.8 years. It remains to be seen whether the benefits of CABG will be sustained over 8 to 10 years and longer, when saphenous vein grafts fail, requiring repeat revascularization. Since the inception of the FREEDOM trial, drug-eluting stents have also evolved. The third-generation drug-eluting stents have shown lower rates of restenosis and repeat revascularization9,10; however, the favorable outcomes with CABG seen in FREEDOM and other studies are unlikely to be completely effected by the type of stents used for PCI.

Alternative approaches, such as hybrid coronary revascularization procedures that include minimally invasive off-pump internal mammary artery grafting to the left anterior descending coronary artery, can be combined with third-generation drug-eluting stents to reduce the risk of stroke and improve postoperative recovery. Furthermore, only 18% of patients in FREEDOM underwent off-pump bypass. Whether off-pump CABG will lead to lower stroke rates in this population will need to be tested.

Further research should help identify those patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary disease who will benefit from PCI; however, until then, CABG appears to be superior in the majority of these individuals. However, a more dynamic patient selection that takes into account stroke risk plus degree of coronary disease will likely be the most beneficial approach. Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the FREEDOM trial is that the findings underscore the importance of a multidisciplinary heart team approach in patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease.

About the Authors

Sachin S Goel, MD, is a Fellow in Interventional Cardiology at the Cleveland Clinic Heart and Vascular Institute, Cleveland, OH. His MD is from the Seth G.S. Medical College and King Edward Memorial Hospital at the University of Mumbai, India. He completed his internship and residency in internal medicine and fellowship in cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. Dr Goel has published several research articles and book chapters and is currently working on structural heart disease research. Mehdi H. Shishehbor, DO, MPH, is the Director of Endovascular Services in the Robert and Suzanne Tomsich Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. He is a specialist in vascular medicine, interventional cardiology, and endovascular intervention. He received his DO from Nova Southeastern University in Florida and a master’s degree in public health at Cleveland State University. He has received several awards including the Thomas J. Linnemeier Spirit of Interventional Cardiology Young Investigator Award. He is presently working on a doctorate in epidemiology at Case Western Reserve University. He is widely published on cardiovascular epidemiology, interventional cardiology outcomes, and techniques, and is coauthor of 2 books on coronary intensive care and cardiac catheterization.

Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes (FREEDOM). N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2375-2384.