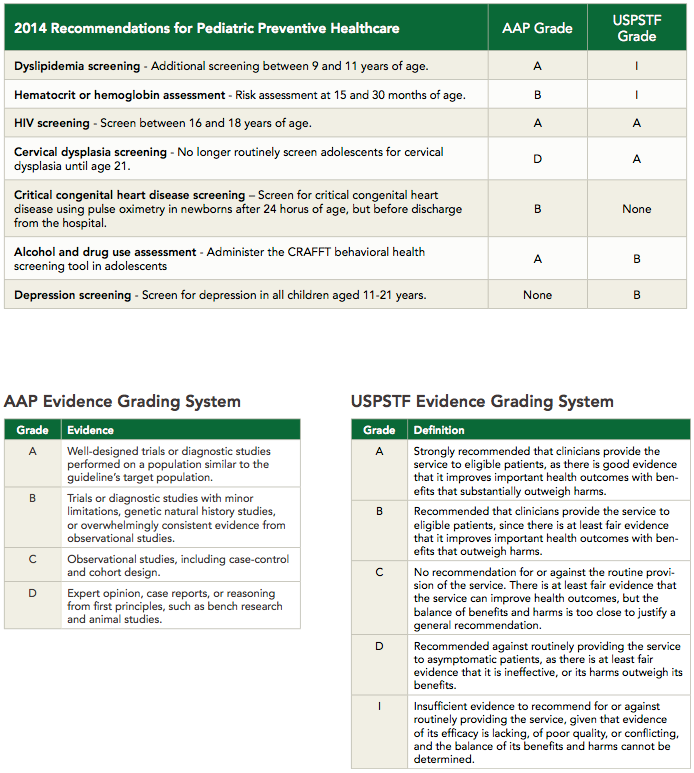

Controversial Changes to Screening Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Care

The American Academy of Pediatrics designed the 2014 Recommendations for Pediatrics Preventive Health Care to guide well-child care, but there is controversy over some of the changes.

Review

Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule Workgroup. 2014 Recommendations for Pediatric Preventive Health Care. Pediatrics. 2014 Feb 24;133(3):568-70. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/3/568.full.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) designed the 2014 Recommendations for Pediatrics Preventive Health Care to guide well-child care. As with all recommendations, the AAP guidelines are not intended to indicate an exclusive course of treatment; instead, they are meant for use in conjunction with clinical judgment of individual circumstances.

Dyslipidemia Screening

Recommendation: Perform additional screenings for dyslipidemia between 9 and 11 years of age, based on AAP-endorsed recommendations from research conducted by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Rationale: Clinical data suggests dyslipidemia in childhood correlates with dyslipidemia in adulthood, with the strongest association shown between late childhood and the third and fourth decades of life.1 Using family history of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD) as the entry point for screening was shown to miss a high proportion of individuals with lipid abnormalities.2 The previous recommendation was for all children to be screened at least once between age 17 and 21.

Controversy: No outcome data has demonstrated benefit in morbidity or mortality from additional dyslipidemia screening. The factors that argue against this screening include limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of lipid-lowering drugs in youth, as well as the influence lipid-lowering medications might have on growth and undermining the motivation for lifestyle changes that are proven to reduce long-term risk.3

Hematocrit or Hemoglobin Assessment

Recommendation: Assess risk for iron deficiency anemia (IDA) at 15 and 30 months of age.4

The known risk factors for iron deficiency in this population include obesity; not attending day care; being of Hispanic descent; feeding with cow’s milk, goat’s milk, or soy milk before 12 months; consuming <2 daily servings of iron-rich foods between 6-12 months of age; a history of premature birth; and, for preschoolers, limited milk intake or <3 daily servings of iron-rich foods. The current recommendations support screening hemoglobin or hematocrit at 12 months of age.

Rationale: The AAP determined selective screening could be performed at any age whenever risk factors for iron deficiency and IDA are identified. Although additional screening is recommended, there have not been any RCTs demonstrating improved outcomes in infant development, behavior, or growth among screened children.5

Controversy: As screening tools, serum hemoglobin and ferritin can have low sensitivities in the first 2 years of life. The implications of addressing low levels of iron remain unclear, but it is assumed to be beneficial for neurological development.

HIV Screening

Recommendation: Offer universal screening for HIV at least once between 16 and 18 years of age when the prevalence of HIV in the patient population is >0.1%. In areas with reduced community HIV prevalence, routine HIV testing is encouraged for all sexually active adolescents, as well as those with other risk factors for HIV.

While previous AAP recommendations encouraged HIV testing only in sexually active youth, the updated statement reflects changes in epidemiology and advances in diagnostic testing. Between 2005 and 2008, the estimated number of HIV/AIDS cases increased among 15- to 19-year-olds and 20- to 24-year olds, and the infectious disease continues to be among the top leading causes of death in the latter age group.6

Rationale: A review by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) showed risk-based HIV screening misses many patients, and there is good evidence for the routine screening of patients seen in high-risk or high-prevalence settings.7 Other studies have demonstrated the cost effectiveness of routine HIV screening, but data addressing the issue in youth remain insufficient.

Controversy: Given the increasing prevalence of HIV among adolescents and the likely cost effectiveness of screening this population for HIV, there is no controversy with this recommendation.

Cervical Dysplasia Screening

Recommendation: No longer routinely screen adolescents for cervical dysplasia until age 21.

Rationale: An analysis modeling of USPSTF recommendations found screening for cervical cancer prior to age 21 is associated with a high number of false-positive test results and an even higher number of colposcopies, but only small gains in life expectancy. Additionally, a large portion of high-grade lesions is estimated to be CIN 2, which is likely to regress in younger women; thus, early screening may result in overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment.8 Other studies have shown that screening women for cervical dysplasia beginning in their early 20s reasonably balances the harms and benefits of screening.9

Controversy: Since this recommendation makes good, cost-effective sense for individuals and the population, there is no controversy.

Critical Congenital Heart Disease (CCHD) Screening

Recommendation: Screen for CCHD using pulse oximetry in newborns after 24 hours of age, but before discharge from the hospital.

Rationale: The previous method of detecting critical congenital heart disease relied solely on prenatal ultrasound examination, and clinical symptoms and physical exam findings in the newborn nursery. This method fails to identify a significant number of cases of CCHD, which leads to late diagnoses and high morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, studies have shown CCHD screening with pulse oximetry in the US could be reasonably cost-effective.10

Controversy: There is none.

Alcohol and Drug Use Assessment

Recommendation: Administer the CRAFFT behavioral health screening tool in adolescents, which asks:

C: Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone — including yourself — who was high or had been using alcohol or drugs?

R: Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to RELAX, feel better about yourself, or to fit in?

A: Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are ALONE?

F: Do you ever FORGET things you did while using alcohol or drugs?

F: Do your family or FRIENDS ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use?

T: Have you gotten into TROUBLE while you were using alcohol or drugs?

Rationale: As a screening tool, CRAFFT has been shown to correlate strongly with substance use in the past 12 months, offering primary care providers (PCPs) practical means of quickly identifying adolescent patients who need more comprehensive assessment or referral to substance abuse treatment specialists.11

Controversy: There is none.

Depression Screening

Recommendation: Screen for depression in all children aged 11-21 years.

Rationale: The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated roughly 20% of patients in this age group are “at risk” for a mental health disorder. Additionally the AAP has recommended that parents of depressed children remove all firearms from the home, as adolescents are prone to impulsive decision-making that allows for increased risk of successful suicide attempts among those with access to firearms. The AAP offers a variety of tools, the simplest of which is the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) that is comprised of the following questions:

Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?

Little interest or pleasure in doing things.

0 = Not at all

1 = Several days

2 = More than half the days

3 = Nearly every day

Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.

0 = Not at all

1 = Several days

2 = More than half the days

3 = Nearly every day

A score ≥3 correlates with a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 75% for depression and should be followed up with a more detailed assessment.

Controversy: Screening for mental health disorders is both critical and challenging, and having a referral and management plan in place when mental health disorders are identified is mandatory. The pharmacologic treatment of depression in the teenage population requires time and skill, as the risk for suicide is higher compared to the general population.

References

1. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines For Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents: Summary Report. 2011 Dec;128:S213-56. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/Supplement_5/S213.full.

2. McCrindle BW, et al. Guidelines for Lipid Screening in Children and Adolescents: Bringing Evidence to the Debate. Pediatrics.p 2012 Aug;130(2): 353-6. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/2/353.short.

3. Gillman MW, Daniels SR. Is universal pediatric lipid screening justified? JAMA. 2012 Jan;307(3):259—60. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1104878.

4. McCann JC, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relation between iron deficiency during development and deficits in cognitive or behavioral function. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Apr;85(4):931-45. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17413089.

5. Pasricha SR. Should we screen for iron deficiency anaemia? A review of the evidence and recent recommendations. Pathology 2012 Feb;44(2):139—47. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22198251.

6. Committee on Pediatric AIDS. Adolescents and HIV Infection: The Pediatrician's Role in Promoting Routine Testing. Pediatrics 2011 Oct;128(5):1023-9. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2011/10/26/peds.2011-1761.abstract.

7. Chou R, et al. Screening for HIV: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Jul 5;143(1):55-73. http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=718529.

8. Kulasingam SL, et al. Screening for Cervical Cancer: A Decision Analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011 May. (Evidence Syntheses, No. 86s.). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92546/.

9. Kulasingam SL, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: a modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013 Apr;17(2):193-202. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23519288.

10. Peterson C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of routine screening for critical congenital heart disease in US newborns. Pediatrics. 2013 Sep;132(3):e595-603. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23918890.

11. Knight JR1, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002 June;156(6):607-14. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12038895.

Click the image to download this handy chart of the 2014 Recommendations for Pediatric Preventive Health Care.

About the Authors

James Kim, MD, is a recent graduate of the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) in Worcester, MA.

He was assisted in writing this article by Frank J. Domino, MD, Professor and Pre-Doctoral Education Director for the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at UMMS and Editor-in-Chief of the 5-Minute Clinical Consult series (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins).